6. Adolescents' relationships with their peers

6. Adolescents' relationships with their peers

Peer relationships are very influential in adolescence. During this time, when young people are developing autonomy from their parents, peers become a significant source of social and emotional support (Gorrese & Ruggieri, 2012). Strong peer attachments have been associated with better psychological wellbeing (Balluerka, Gorostiaga, Alonso-Arbiol, & Aritzeta, 2016; Gorrese, 2016). In addition to attachment, the attitudes of adolescents' friends can have both positive and negative influences on a range of behavioural, social-emotional and school outcomes (Alexander, Piazza, Mekos, & Valente, 2001; Ryan, 2001).

When adolescents experience problems in their peer relationships, such as bullying, it can have significant psychological, physical, academic and social-emotional consequences for both victims and perpetrators (Craig & Pepler, 2003). The quality of adolescents' attachments with their peers and the attitudes of their friends may be associated with their likelihood of being involved in bullying.

Given the significance of peer relationships for adolescents' development, it is important to understand the nature of these relationships. The purpose of this chapter is to provide a snapshot of the peer relationships of Australian adolescents, by describing peer attachments, peer group attitudes, and peer problems as they are reported by young people in mid-adolescence. In addition, the relationship between features of adolescents' peer relationships and their status as a victim and/or perpetrator of bullying is examined.

Box 6.1: Peer attachments

The quality of peer attachments was measured in the LSAC K cohort at Waves 5 and 6 using items adapted from the Peer Attachment Scale of the Inventory of Peer and Parental Attachment. The scale included in LSAC is made up of two subscales: trust (four items) and communication (four items).

- Trust reflects the degree of mutual understanding and respect in peer relationships. Adolescents rate how well statements such as 'I feel my friends are good friends' and 'I trust my friends' reflect their peer relationships on a five-point scale from '1 = Almost always true' to '5 = Almost never true'. At age 14-15 years old: mean (SD) = 6.7 (3.0), range: 4-20; and at 12-13 years old: mean (SD) = 6.4 (3.1), range: 4-20. (*SD: standard deviation).

- Communication reflects the extent and quality of communication in peer relationships. Adolescents rate how well statements such as 'My friends sense when I'm upset about something' and 'My friends encourage me to talk about my difficulties' reflect their peer relationships on a five-point scale from '1 = Almost always true' to '5 = Almost never true'. At age 14-15 years old: mean (SD) = 8.8 (3.6), range: 2-20; and at 12-13 years old: mean (SD) = 8.6 (3.8), range: 3-20. (*SD: standard deviation).

- A measure of overall peer attachment was also created by summing across all items. At age 14-15 years old: mean (SD) = 15.5 (6.0), range: 8-40; and at 12-13 years old: mean (SD) = 14.9 (6.3), range: 8-40. (*SD: standard deviation).

Higher scores on the trust, communication and overall peer attachment measures reflect poorer peer attachments. Scores on each scale were divided into two groups with attachments scoring one standard deviation above the mean categorised as 'low peer attachment', and all other scores labelled 'relatively high peer attachment'. The categorisation was done for the whole sample separately for both age groups.

6.1 Positive peer attachments in adolescence

Peer attachments refer to the specific bond between one or a few peers. Secure peer attachments are characterised by bonds that satisfy adolescents' basic needs for emotional support and a 'safe haven' (Balluerka et al., 2016). Some research shows that girls tend to report higher levels of attachment to their peers than do boys. This may be due to differences in the nature of female and male friendships; with girls placing more importance on closeness and open communication in their friendships than boys (Gorrese & Ruggieri, 2012).

The quality of peer attachments in girls and boys was examined at two time points in early adolescence - around the time they started secondary school (at age 12-13) and two years later (at age 14-15). The beginning of secondary school is an important transition for adolescents, and this change in school context can result in rapid changes in friendship groups and peer social support networks. This can potentially lead to instability in peer attachments (Desjardins & Leadbeater, 2011).

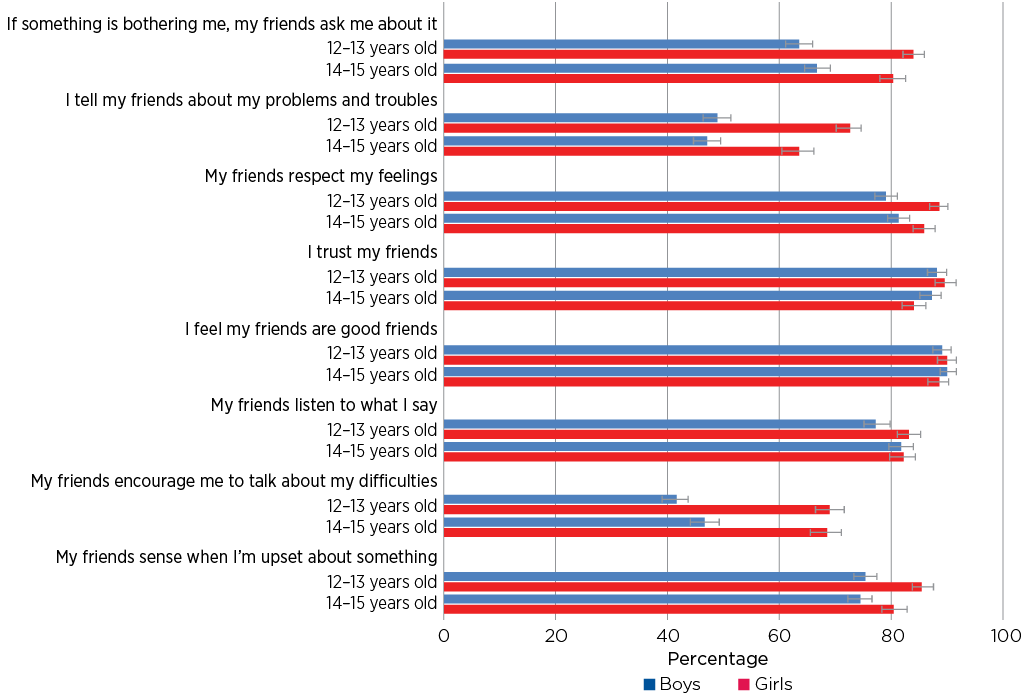

At 12-13 and 14-15 years of age, 80-90% of adolescent boys and girls reported having good friends who they trusted and who they felt respected their feelings and listened to them (Figure 6.1). In both age groups, more than three quarters also reported that their friends sensed when they were upset about something.

Fewer adolescents reported that they told their friends about their problems and troubles, and that their friends encouraged them to talk about their difficulties. However, more girls than boys said that these were characteristics of their peer relationships; for example, at ages 12-13 and 14-15, almost 70% of girls and around 45% of boys said their friends encouraged them to talk about their difficulties.

More girls than boys reported high levels of communication in peer relationships (Table 6.1). For example, at age 12-13, 91% of girls and 78% of boys reported high levels of communication with their peers. High levels of trust with peers was reported by around 85% of boys in both age groups, and by 88% and 85% of girls at ages 12-13 and 14-15 respectively.

Figure 6.1: Peer attachment items, by gender

Note: 12-13 years old: Boys: n = 1,952; Girls: n = 1,887; 14-15 years old: Boys: n = 1,701; Girls: n = 1,643.

Source: LSAC Waves 5 and 6, K cohort, weighted

Source: LSAC Waves 5 and 6, K cohort, weighted

To further explore stability in peer attachments during adolescence, the proportion of adolescents who reported high peer attachment at neither, one of or both ages 12-13 and 14-15 were examined (Table 6.2). The majority of adolescents (75% in total) reported high levels of peer attachment at both 12-13 and 14-15 years; while around one fifth reported high peer attachments at only one of these time points (Table 6.2). Only 5% of adolescents reported no high peer attachment at either age. More girls than boys (80% versus 70%) reported high peer attachment at both 12-13 and 14-15 years.

Overall, adolescent reports of their levels of peer attachment were very similar and stable at ages 12-13 and 14-15. Given this stability, the remainder of the chapter will focus on data collected about peer relationships at age 14-15.

Source: LSAC Waves 5 and 6, K cohort, weighted

6.2 Peer group attitudes

The attitudes of an adolescents' peer group can have both positive and negative influences. While adolescents tend to select friends who have similar attitudes to them, they are also strongly influenced by the behaviour of their peers (Ryan, 2001). Research shows that adolescents are more likely to engage in risky behaviours, such as smoking, if they have friends who engage in those behaviours (Alexander et al., 2001). Alternatively, having high-achieving friends can influence adolescents' own academic achievement and enjoyment of school (Ryan, 2001).

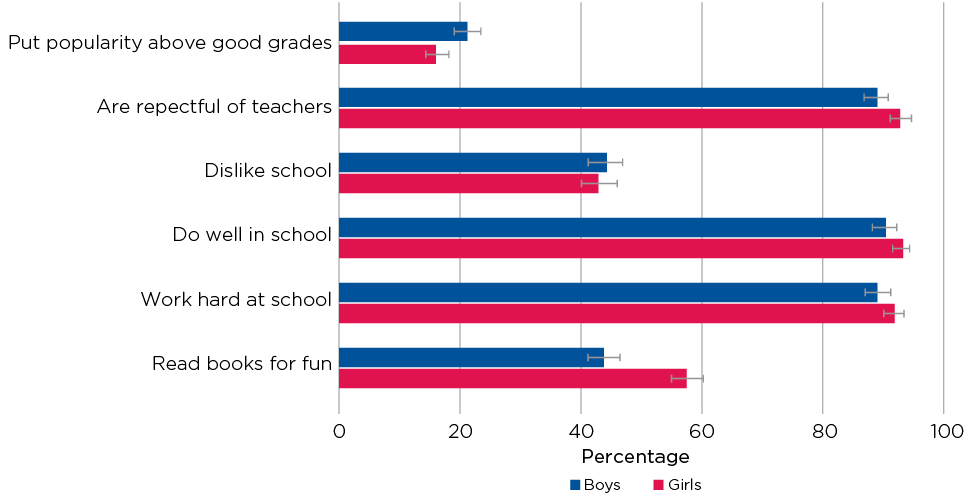

At age 14-15 years, the majority of adolescents reported that at least some of their friends exhibited a positive attitude towards school and academic achievement (Figure 6.2). For instance, around 90% of girls and boys spent time with peers who were respectful of teachers, did well in school and worked hard at school (Figure 6.3). Almost 60% of girls and 44% of boys reported that their friends read books for fun. On the other hand, over 40% of girls and boys reported that their friends dislike school, and around one in five said that their friends put popularity above grades.

Figure 6.2: Proportion of 14-15 year olds who reported positive academic attitudes as being true for some, most or all of the peers they spend time with

Note: Boys: n= 1,703; Girls: n = 1,643.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Box 6.2: Peer group attitudes

Peer group attitudes were measured in the LSAC K cohort at Wave 6 using items adapted from the 'What my Friends are Like' questionnaire and the Australian Temperament Project. Respondents were asked to indicate whether a range of positive and negative attitudes reflected the kids they spent time with (from school, their neighbourhood or elsewhere) on a five-point scale from '1 = None of them' to '5 = All of them'.

The peer group attitudes are categorised into four types of attitudes, and scale scores were obtained for each of these by summing responses across items (higher scale scores indicated peer groups that were higher on that specific characteristic):

- Positive orientation toward academic achievement (six items): for example, 'Kids you know read books for fun' and 'Kids you know work hard at school'. Two items were reverse coded for scale calculation ('Kids you know dislike school' and 'Kids you know put popularity above good grades'). Mean (SD) = 21.9 (3.8), range: 6-30. (*SD - standard deviation).

- Peer group moral behaviour (seven items): for example, 'Kids you know get into trouble' and 'Kids you know are mean to other kids'. All items were reverse coded for scale calculation, with the exception of 'Kids you know go to religious services'. Mean (SD) = 28.7 (3.3), range: 5-35. (*SD - standard deviation).

- Peer group risky behaviour (5 items): for example, 'Kids you know drink alcohol' and 'Kids you know have broken the law'. Mean (SD) = 6.5 (2.7), range: 5-25. (*SD - standard deviation).

- A measure of total positive peer group attitudes including all items measuring positive orientation toward academic achievement and peer group moral behaviour. Mean (SD) = 57.5 (6.9), range: 8-73. (*SD - standard deviation).

Scores on each of the four scales were divided into two groups with peer groups scoring one standard deviation below the mean categorised as 'low' on each of the attitudes, and all other scores categorised 'high' on the specific attitudes. The categorisation was done for the whole sample separately for both age groups.

Figure 6.3: Adolescents who said they had friends who were respectful of teachers and worked hard at school

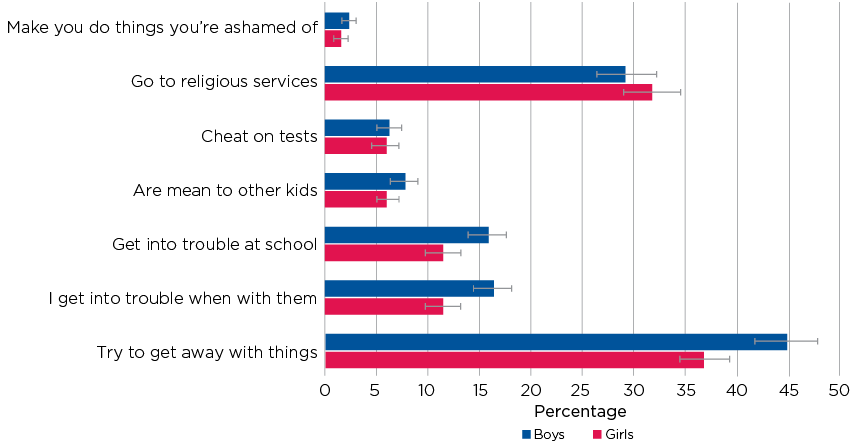

For most adolescents, the moral attitudes of their peers were not problematic. Only around 7% of girls and boys reported that their friends cheated on tests and were mean to other kids, while 11% of girls and 16% of boys reported that their friends got into trouble at school (Figure 6.4). Only a tiny proportion of girls and boys (2%) said that their friends made them do things they were ashamed of. Around 40% of girls and boys reported that their friends tried to get away with things but for many this could reflect normal adolescent behaviour of 'testing the boundaries'.

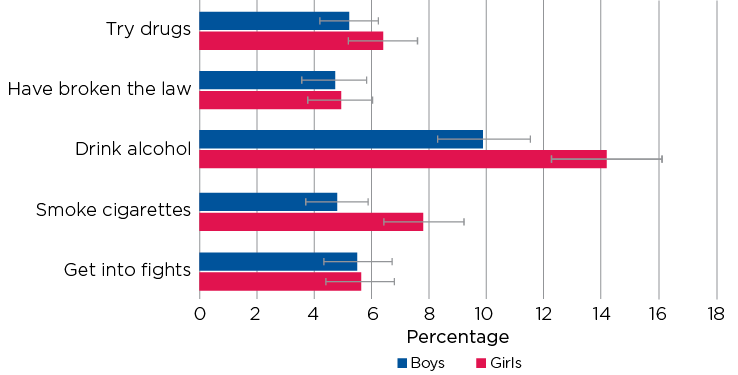

Around 5-7% of girls and boys said that some, most or all of their friends engaged in risky behaviours such as trying drugs, smoking cigarettes, breaking the law and getting into fights (Figure 6.5). About 14% of girls and 10% of boys said they had friends who drank alcohol, which is similar to the proportion of 14-15 year olds who previously reported having consumed an alcoholic drink (Homel & Warren, 2016).

Overall, 86% of girls and 82% of boys reported that their peer groups were characterised by high levels of positive attitudes (Table 6.3). More specifically, a positive orientation toward academic achievement characterised the peer group of 85% of girls and 79% of boys. Slightly more girls (88%) than boys (80%) reported that their friends exhibited high levels of positive moral behaviour. Around one in eight girls and boys aged 14-15 reported that their friends engaged in high levels of risky behaviours.

Figure 6.4: Proportion of 14-15 year olds who reported moral behaviour attitudes as being true of some, most or all of the peers they spend time with

Note: Boys: n = 1,703; Girls: n = 1,643.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Figure 6.5: Proportion of 14-15 year olds who reported risky behaviour attitudes as being true of some, most or all of the peers they spend time with

Note: Boys: n = 1,703; Girls: n = 1,643.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Peer group attitudes by peer attachments

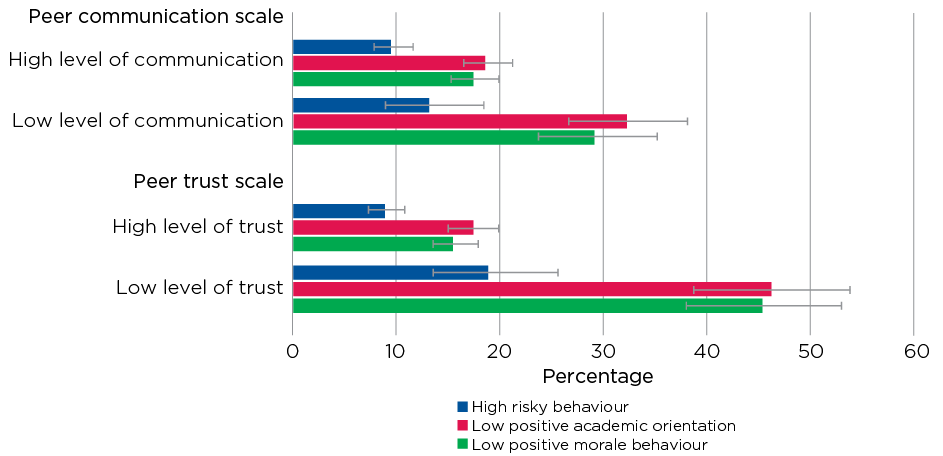

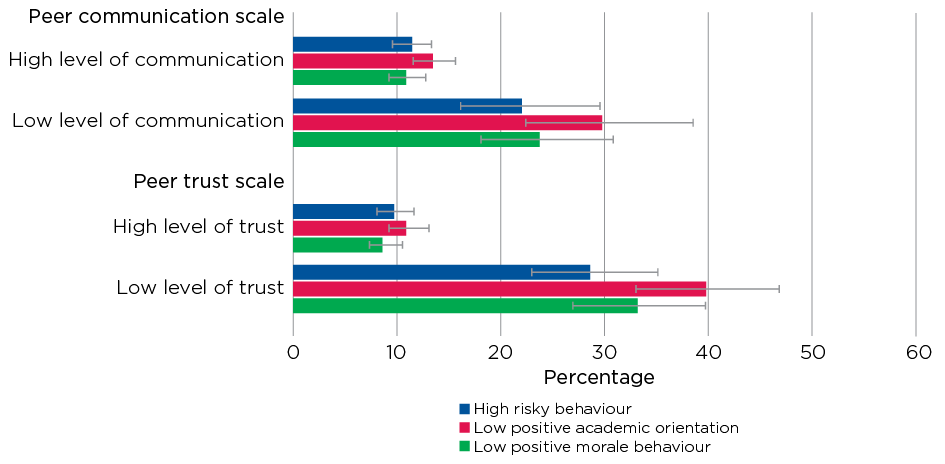

Adolescent boys and girls with poorer peer attachments were more likely to report that their friendship group is characterised by high levels of risky behaviour and low levels of positive attitudes (Figure 6.6 and Figure 6.7). For instance, around 35% of girls and 45% of boys with low levels of trust in their peer attachments reported that their friends demonstrated lower levels of positive moral behaviours. However, low levels of positive moral behaviour characterised the friendship groups of fewer than 10% of girls and 15% of boys who reported high levels of trust in their peer attachments. Around 30% of boys and girls with low levels of peer communication reported that their peer groups demonstrated few positive attitudes towards academic achievement, compared to 13% of girls and 19% of boys with peer attachments characterised by high levels of communication.

Figure 6.6: Boys' peer group attitudes by peer attachments at age 14-15

Note: n = 1,703.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Figure 6.7: Girls' peer group attitudes by peer attachments at age 14-15

Note: n = 1,643.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

6.3 Adolescents' experiences of bullying

While positive peer relationships are associated with good adolescent adjustment and wellbeing, problems in adolescent peer relationships can be detrimental. Bullying in particular is a major adolescent health concern internationally (Craig et al., 2009). It can take direct forms such as physical and verbal aggression and indirect forms such as social exclusion (Craig et al., 2009). Gender differences have been found in the types of bullying experienced by adolescents. Boys are more likely to experience physical aggression, whereas girls are more likely to experience social aggression such as isolation and gossip (Carbone-Lopez, Esbensen, & Brick, 2010; Craig & Pepler, 2003).

Box 6.3: Bullying victims and perpetrators

Bullying has been defined as intentional and repeated aggressive behaviour towards a peer that causes them harm (Smith et al., 1999). At Wave 6, study children (age 14-15 years) were asked to report on their experiences of both bullying victimisation and perpetration.

LSAC study children were asked whether or not in the past month (30 days) they were the victim (e.g. 'kids hit or kicked me on purpose', 'kids said mean things to me or called me names') or perpetrator (e.g. 'I hit or kicked someone on purpose', 'I said mean things to someone or called someone names') of a range of bullying acts. Those who reported being victims or perpetrators of bullying were also asked how frequently the bullying had occurred in the past month from '1 = once or twice' to '3 = several times a week'.

Based on their responses to these items, adolescents were considered to have been a victim of bullying if they reported being victim to an act of bullying on at least a single occasion in the last month. Adolescents were considered to have been a bully if they reported perpetrating an act of bullying on at least a single occasion in the last month.

At age 14-15 years, almost one in five adolescents (19%) reported being a victim of bullying in the previous month. The proportion of adolescents who were victims was similar for girls and boys (about 19%). A smaller proportion of adolescents reported bullying others (7% in total), with about 5% of girls and 10% of boys reporting that they had bullied others in the previous month. Around 6% of adolescents reported bullying others and also being a victim.

Looking at more specific acts of bullying that adolescents reported being the victim of:

- The most common act across both boys (16%) and girls (23%) was someone saying mean things or name calling (Figure 6.8).

- More boys than girls reported experiencing physical aggression; for example, 14% of boys and 6% of girls reported being hit or kicked on purpose.

- Acts of social exclusion were more common amongst girls; for example, 13% of girls and 5% of boys reported that someone 'tried to keep others from being my friend'.

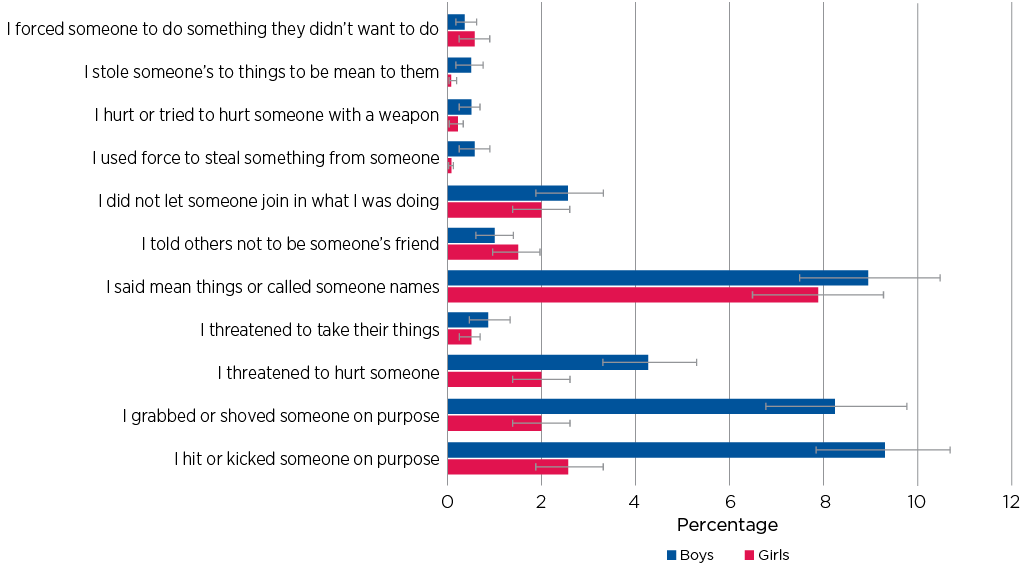

The most common act of bullying that both boys (9%) and girls (8%) reported perpetrating was saying mean things to someone or name calling, which is not surprising, given this was also the most frequent act of bullying reported by victims (Figure 6.9). More boys than girls reported being physically aggressive towards others. For example, 8% of boys and 2% of girls reported grabbing or shoving someone on purpose. Around 4% of boys and 2% of girls had threatened to hurt someone. A similar proportion of boys and girls (1-3%) reported engaging in acts of social exclusion, such as not letting someone join in with what they were doing or preventing others from being friends with their victim. All other bullying acts were reported by less than 1% of 14-15 year olds.

Figure 6.8: Proportion of 14-15 year olds who reported being a victim of bullying in last 30 days, by gender

Note: Boys: n =1 ,702; Girls: n = 1,641.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Figure 6.9: Proportion of 14-15 year olds who reported bullying in last 30 days, by gender

Notes: Boys: n = 1,702; Girls: n = 1,641.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Associations between bullying and features of adolescent peer relationships

Research suggests that high levels of peer attachment and having close friends helps to protect adolescents from involvement in bullying (Goldbaum, Craig, Pepler, & Connolly, 2003; Murphy, Laible, & Augustine, 2017). In addition, high levels of social support from peers may buffer the negative impact of bullying on adolescents' emotional wellbeing (Hodges, Boivin, Vitaro, & Bukowski, 1999; Papafratzeskakou, Kim, Longo, & Riser, 2011).

The types of peers that adolescents are friends with may also be associated with their bullying involvement. For instance, research suggests that bullies tend to hang out with other bullies, and peers who are aggressive or antisocial (Espelage & Holt, 2001). Victims of bullying are also more likely to be friends with other children who have also been victimised or who lack characteristics to successfully defend against bullying (Rodkin & Hodges, 2003).

The association between adolescents' status as a victim or bully in the past month and their peer attachments and peer group attitudes was examined, taking into consideration other factors such as self-efficacy, empathy and prosocial behaviour.

Table 6.4 shows that the odds of being a victim of bullying at age 14-15 were:

- halved for adolescents with high peer attachments compared to those with low peer attachments

- two times higher for adolescents whose friends were engaged in high levels of risky behaviours compared to those whose friends did not engage in these behaviours

- halved for those whose friendship group was characterised by high levels of moral behaviour compared to low levels of moral behaviour

- reduced by 30% for adolescents whose friends valued academic achievement, compared to those whose friends did not value academic achievement.

The odds of having been a bully at age 14-15 were:

- two times higher for adolescents whose friends engaged in risky behaviours compared to those whose friends did not engage in these behaviours

- reduced by 60% for adolescents whose friendship group was characterised by high levels of moral behaviour, compared to those whose friendship group had lower levels of moral behaviour

- reduced by 40% for girls compared to boys.

The odds of being a victim and a bully were similar to the odds of being a bully.

Notes: n = 3,288. Odds ratios (OR) are shown. Estimates are adjusted for family socio-economic status and adolescents' self-reported self-efficacy, empathy and prosocial behaviour to account for factors that may potentially explain the association between peer relationships and bullying. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Summary

This chapter provides a picture of the quality of peer relationships of Australian children around the time of mid-adolescence and sheds some light on the attitudes of adolescents' friends. Understanding who adolescents choose to spend their time with can help us to understand their own attitudes and behaviours. The majority of adolescents (86% of girls and 82% of boys) reported that their friendship groups displayed positive attitudes, including positive attitudes towards school and academic achievement and positive moral behaviour. Only a small proportion, around one in eight, reported that high levels of risky behaviours characterised the friends they spent time with.

Bullying is a major source of stress arising from adolescents' interactions and relationships with their peers, and a major public health concern facing schools and policy makers. The findings from this chapter show that around one fifth of adolescents aged 14-15 reported being the victim of bullying in the past month. However, only around 7% of adolescents admitted to being perpetrators of bullying.

The data show that having positive peer attachments, friends with a positive orientation towards academic achievement or high levels of moral behaviour were each associated with a reduced likelihood of being a victim of bullying. Conversely, having friends who engaged in high levels of risky behaviours was associated with a greater likelihood of having been the victim of bullying. Only peer group attitudes, and not peer attachment, were associated with being a perpetrator of bullying. Adolescents whose peers had shown high levels of moral behaviour were less likely to have reported that they had bullied someone, while those whose peers engaged in more risky behaviours were more likely to have reported that they had been a bully.

This chapter raises a number of important questions for future work in this area. A better understanding of the causal role that different features of adolescents' friendships play in their social-emotional development will help to inform how peer relationships can be targeted by efforts to promote adolescent wellbeing and prevent and treat the development of psychological difficulties.

References

Alexander, C., Piazza, M., Mekos, D., & Valente, T. (2001). Peers, schools, and adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health, 22-30.

Balluerka, N., Gorostiaga, A., Alonso-Arbiol, I., & Aritzeta, A. (2016). Peer attachment and class emotional intelligence as predictors of adolescents' psychological well-being: A multilevel approach. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 1-9.

Carbone-Lopez, K., Esbensen, F. -A., & Brick, B. T. (2010). Correlates and consequences of peer victimization: Gender differences in direct and indirect forms of bullying. Youth Violence & Juvenile Justice, 8(4), 332-350. doi:10.1177/1541204010362954

Craig, W., Harel-Fisch, Y., Fogel-Grinvald, H., Dostaler, S., Hetland, J., Simons-Morton, B. et al. (2009). A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. International Journal of Public Health, 2, 216.

Craig, W. M., & Pepler, D. J. (2003). Identifying and targeting risk for involvement in bullying and victimization. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 48(9), 577-582

Desjardins, T. L., & Leadbeater, B. J. (2011). Relational victimization and depressive symptoms in adolescence: Moderating effects of mother, father, and peer emotional support. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(5), 531-544.

Espelage, D. L., & Holt, M. K. (2001). Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: Peer influences and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 2(2/3), 123-142.

Goldbaum, S., Craig, W. M., Pepler, D., & Connolly, J. (2003). Developmental trajectories of victimization: Identifying risk and protective factors. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 19(2), 139-156.

Gorrese, A. (2016). Peer attachment and youth internalizing problems: A meta-analysis. Child & Youth Care Forum, 45(2), 177-204.

Gorrese, A., & Ruggieri, R. (2012). Peer attachment: A meta-analytic review of gender and age differences and associations with parent attachment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(5), 650-672.

Hodges, E. V. E., Boivin, M., Vitaro, F., & Bukowski, W. M. (1999). The power of friendship: Protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 94-101

Homel, J., & Warren, D. (2016). Parental influences on adolescents' alcohol use. Australian Institute of Family Studies (Ed.), The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children: Annual statistical report 2016, (pp. 61-84). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Murphy, T. P., Laible, D., & Augustine, M. (2017). The Influences of parent and peer attachment on bullying. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(5), 1388-1397. doi:10.1007/s10826-017-0663-2

Papafratzeskakou, E., Kim, J., Longo, G. S., & Riser, D. K. (2011). Peer victimization and depressive symptoms: Role of peers and parent-child relationship. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 20(7), 784-799. doi:10.1080/10926771.2011.608220

Rodkin, P. C., & Hodges, E. V. E. (2003). Bullies and victims in the peer ecology: Four questions for psychologists and school professionals. School Psychology Review, 32(3), 384-400.

Ryan, A. M. (2001). The peer group as a context for the development of young adolescent motivation and achievement. Child Development, 4, 1135.

Smith, P., Morita, Y., Junger-Tas, J., Olweus, D., Catalano, R. F., & Slee, P. T. (1999). The nature of school bullying: A cross-national perspective. London: Taylor & Frances/Routledge.