Recently, I found myself longing to reread John Steinbeck’s Log from the Sea of Cortez. I first read it when I was a teenager studying one of his novels at school; anxious for me to succeed, my parents purchased other Steinbeck books in the cheap Pan editions featuring naïve illustrations constrained by circular borders, as if seen through a telescope. The book is the author’s account, a decade after the event, of his travels in 1940 with marine biologist Ed Ricketts, who would become the model for ‘Doc’ in Cannery Row. Under the pretext of a loosely conceived scientific expedition, the men hire and equip a small purse seiner, a fishing boat, and set out from Monterey, in northern California, for the Sea of Cortez (also known as the Gulf of California), between the Baja California Peninsula and Mexico. Over six weeks, they pull creatures from the low coastal waters, to collect specimens for Rickett’s marine biological business, but also for the sheer pleasure of gathering them in their plenitude and seeing how these small animals propel themselves and behave. It is from this from such close observation, surely, that Steinbeck conceived the metaphor for storytelling that would open Cannery Row:

There are certain flatworms so delicate that they are almost impossible to catch whole for they will break and tatter under the touch. You must let them ooze and crawl of their own will onto a knife blade and lift them gently into your bottle of sea water. And perhaps that might be the best way to write this book — to open the page and let the stories crawl in by themselves.

I reread The Log from the Sea of Cortez with a kind of hunger; for the wonders it catalogues, but also for the calm, certain joy of its writing.

This year, I have also found myself picking up and putting aside the books I have collected about the French expedition of 1800-1804 to Australia for a long-stalled novel about the scientists, artists and sailors Napoleon sent in two mighty caravels to extend his empire’s grand intellectual project. Captain Nicolas Baudin is the story’s tragic hero but my interest always settles on the illustrations of Petit and Lesueur, two crewmen who would become the expedition’s artists by default after many of the crew left the boat at Isle de France (present day Mauritius).

Among these images, I feel myself called by Lesueur’s watercolour paintings of jellyfish: ethereal, mysterious, yet weirdly adamant. To look at them is to feel that you are looking at the mystery of life itself: some are faint and ghostly, floating scraps of bare existence, others, with their brightly mottled bells and ruffs of tentacles, like small monsters in eighteenth-century garb. Like Steinbeck’s flatworms, they, too, are compelling metaphors for the magic of artistic process: reanimations of dead creatures whose colours have faded within moments of collection, painted with a fine brush to live a second life on the skin of a dead calf that has itself undergone a transformation into vellum. They are also emissaries from a century of wonder and seas untroubled by any sense of being imperilled.

I was returning to these books because I needed to immerse myself in their world of long-gone natural abundance; a place of astonishing throngs, when things existed according to their own mysterious logic. Recently, I was walking through the Botanic Gardens on a sunny-misty spring Sydney day with my children when I had an inkling of this past again. An Indigenous heritage tour was coming to its end and we joined it. One of the objects the guides passed around from a custom-made wooden box was a shell—chalky, as large as a saucer, and miraculously dense, even without the meat of the creature that once lived inside it. Oysters like this, the guides said, had once thrived around the harbour. This was a surprise. I had grown up imagining the middens that stood around its edges—and whose shell grit, I realise now, formed part of the particulate grit beneath my feet in the playgrounds around Wollstonecraft where I played—were made up of the small Sydney rock oysters with rusty-coloured frills that you see today clustering around the sandstone walls and pylons of the harbour. Now I had to reconceive of them as containing these mighty remnants. I had also to revise my lifelong understanding of middens as mere garbage dumps because they also existed for the Gadigal, the guides said, as a kind of index. If these huge shells were at the top of the heap they would not be taken for a certain period, to preserve the supply; but the colonists, with no such system, soon ate them out of existence and such giants are no longer to be found.

Back home, I went online to look for more information about these large shellfish. Instead, I found, unspooling page after page, articles about the worldwide decline of oysters. A newspaper report from 2011 described a scientific study, which found that wild oysters were already becoming ‘functionally extinct’. Because 85 per cent of oyster reefs had disappeared around the world, due to overfishing, oysters were at ‘less than 10 per cent of their prior abundance in most bays and ecoregions’. This led me to other articles discussing how oysters, among other molluscs, including lobsters, are at even more catastrophic risk (if that is possible) from ocean acidification, as increased levels of carbon dioxide in the sea thin and threaten to dissolve their calcium-carbonate-based shells. Google images brought up photographs as ethereal as Lesueur’s watercolours, of pteropod shells (a kind of swimming snail also known as a ‘sea butterfly’), disappearing from one image to the next as their shells thinned, their glassy transparency becoming etched and then fragmenting.

This is a too-familiar story when we read about nature, which is under tremendous stress, its wild populations thinning, even in its remotest corners. It’s not hard to think of historical examples of decimation: passenger pigeons, buffalo, the cod banks of the north Atlantic; while on Mauritius, that island of failure where Baudin and Flinders would both come to grief, the dodo had already been hunted to extinction by 1662. Yet these seem almost small-scale, minor premonitions, compared to the era we’re now living through, in which species are declining at such a rate that the phenomenon has been named the ‘sixth extinction’: that is, the sixth mass extinction event since life on earth began 3.7 billion years ago. Yet this time, instead of being caused by an ice age or volcano or meteor, the loss is caused by us.

In just the last four decades, less than my own lifetime, we have lost an estimated 58 per cent of species worldwide: mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and insects, an extinction rate which scientists estimate is 100 to 1000 times the natural rate without human involvement. And yet it can be hard to ‘see’ this decline, when we measure it by the small scale of a human life; when such things are, for many of us, in the distance; and when we only find ourselves noticing things we haven’t seen for some time, even if they were once ubiquitous. Like the house sparrow. It’s only when I am in Melbourne, where they seem to still thrive, or in small parts of Sydney, like Clovelly Bay, hearing them chirp in the low coastal scrub, that I realise their cheerful presence has all but disappeared from the city’s parks.

When had I been surrounded, I wondered, by an obvious abundance of wild creatures? Visiting the country around Tenterfield every Christmas with my family in the 70s, I have clear memories of seeing clusters of pademelons and wallabies in quiet conference around the water troughs in paddocks—pointed out by local farmers as ‘pests’. Snorkelling on the Great Barrier Reef, and experiencing the out-of-body sensation of being suspended among fish in vertiginous strata, from the tiny blue and gold fish I think of as the ‘heavenly hosts’, hanging in the bright sunlit water near the surface, to the larger parrot fish, puppyish and social, grazing on the coral heads below. I remember prawns jumping from the Shoalhaven River when I have played torchlight across the water and the less romantic childhood sound of the wet bodies of moths and crickets hitting the car windscreen when driving through the bush at night (that ritual of cleaning them from the glass at service stations is something else I haven’t thought of for decades).

A great joy of the last fifteen years back in my hometown of Sydney has been the dusk migration of its flying fox colonies over the eastern suburbs where I live — their ‘windrowing’, as Les Murray puts it in his poem ‘The Flying-Fox Dreaming’ as they home on ‘ripe tree beacons’. Remembering these sights, I also recall reading somewhere that the kinds of animals we’ve witnessed, and lived around, make us different people: that is, humans who were surrounded by passenger pigeons are different people for that reason to those of us who no longer are. I like to think that these flying foxes are part of who I am.

And yet—a twenty-first-century question—how abundant is abundant? Since the flying foxes were moved on from their camp in Sydney’s Botanic Gardens in 2012, they seem less prolific, now ‘going on out continually over horizons’ (as Murray puts it) in a reverse direction, from west to east. Watching them I feel out of whack; I miss that terrific drama I wrote about in Sydney, when they boiled up from the Gardens each sunset like black ash from a fire. Nor do they seem to flock in quite the same numbers; my children, born in 2011, are yet to be kept awake by loud squabbling and piping in the Moreton Bay fig outside our apartment in fruiting season, so extraordinary when we first moved here. And yet I knew, even as I wrote that description ten years ago, that the population I was witnessing was itself diminished, displaced into the city in the late 1980s by the destruction of habitat in the state’s inland bush and the city’s suburban outskirts. Some years ago, in the Mitchell Library, I ordered up a yellowing clippings file on flying foxes from its old handwritten catalogue card drawers. A newspaper article from mid-last-century described vast numbers of the animals wheeling over farmers’ sheds in central New South Wales, attracted to the smell of the honey they were decanting.

Still, it is hard to miss what you haven’t seen. This problem of only being able to judge loss within our own lifespan has a name: ‘shifting baseline syndrome’. Fisheries scientist Paul Daniel coined the term in 1995 when he noticed that each generation of scientists tends to use the status of fish stocks during its own lifetime as the baseline from which it conducts further studies. Psychologist Peter H Kahn has also described this phenomenon in which each generation accepts its degraded environment as normal as ‘environmental generational amnesia’. In his book Wild Ones, journalist Jon Mooallem writes about taking his very young daughter with him to see and write about America’s engendered species in order to extend this baseline, in this one small human at least. Nevertheless, I feel for Mooallem’s daughter: such knowledge is an ambiguous gift. Like her, I can’t claim to have had the luxury of obliviousness during my childhood: as my mother was also preoccupied, presciently, with environmental damage and extinction. At Mooallem’s daughter’s age I was addicted to Armand Denis’s Wildlife Magazine, which, along with documenting life with animals in Africa, often showed the depredations of hunting and poaching. Even so, it has come as a terrible shock to come learn this year that the ‘common’ African animals I was reading about, like giraffes and wild dogs, are now threatened.

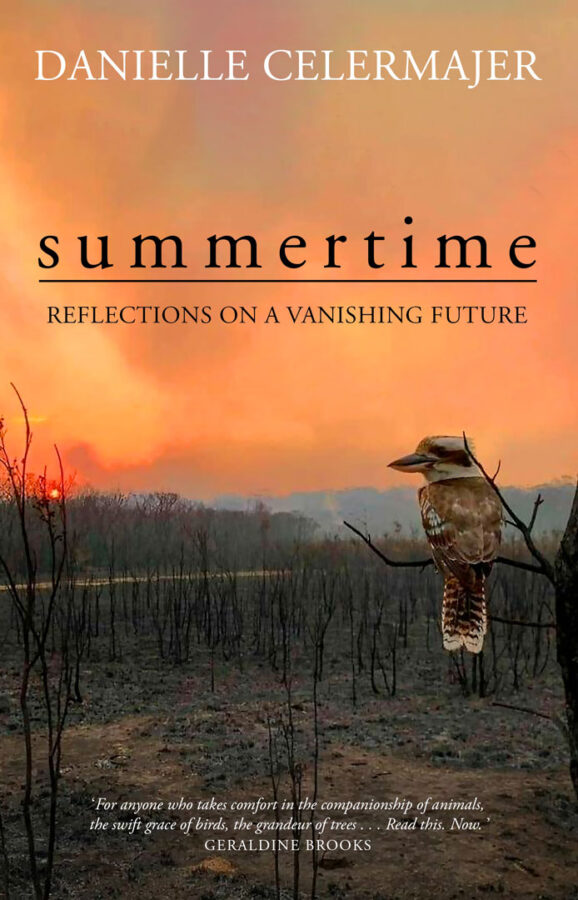

I’m not the first to observe that this knowledge means our encounters with the natural world now have a darker emotional texture. The ongoing crisis of global warming, with its delayed yet already tangible effects, means that even what seems beautiful is suspect, impermanent beyond the predictable cycles of life and death. In 2003, Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht coined a term for this existential melancholy: ‘solastalgia’. An existential melancholy produced by the negative transformation of a home environment, solastalgia is ‘the homesickness you have when you are still at home’. Even pleasure casts shadows. When I eat sushi, I wonder if I will be part of a last generation to taste tuna (perhaps even the flesh of any fish). A friend confesses to visiting Sydney’s Nielsen Park with his children and envisaging the beach, and all its familiar landmarks and memories, submerged by rising seas.

In fact, it was while watching flying foxes on a friend’s roof garden in Kings Cross this year, during a strangely endless summer, that I realised my own solastalgia had become a permanent state. One of the women I was with is a science writer; another works, with cautious hope, in the non-profit sector. The flying foxes moved across the sky with their odd stop-motion action, like footage from an old movie camera; some dipped close enough for us to see the blaze of fur on their chests, the same red-brown as the velvet inside a banksia pod. Something has crossed over for me this last year, my science writer friend said; I don’t think things will be okay. We each felt that way. Things had changed for me, I told my friends, when I heard the news about the Great Barrier Reef—that we had killed off the largest living organism on the planet—as I walked in the streets of a Buenos Aires in the grip of an unseasonal month of rain. (The city’s weather had been changing, my university colleagues said, since the rainforests in the country’s north were replanted with soy bean crops; just as a year earlier, in Chile, an army officer my age mentioned that the dessicated Cerro Santa Lucía, where we stood looking down at La Serena, had been a lush green during his childhood, but was now—like the rest of the region—in a state of semi-permanent desertification).

There is a strong feeling among scientists that human activity has created a new geological era, though this is yet to be ratified, and debate is far from settled about where to plant the golden spike between the Holocene and what will likely be called the Anthropocene. However, while this name has established itself informally, it’s not uncontroversial, particularly because it infers that all people are equally responsible for these vast changes. Some academics have instead proposed the terms Capitalocene (to make it clear that our growth-addicted global economy is largely to blame); the Thermocene or Carbocene (emphasising CO2 accumulation) or even the Thanatocene (concentrating on the role of wars).

For me the name that rings most achingly is the Age of Loneliness. Not only will the world be less rich without its many wild creatures, but we face a future in which we are thrown back only upon ourselves. As John Berger, and many writers since, have pointed out, humans have used animals to think with since we first began to paint their drawings on cave walls with our blood; they entered our lives, Berger writes, not as our subjects but as ‘messengers and promises’, their presences magical oracular, sacrificial. We study them when we are tiny and learning to become human: polar bears, alligators, elephants, apes, and pets fill our nursery shelves and picture books. With their different life spans, they even help us measure time. I have always loved St Bede’s description of human life as being like ‘the swift flight of a sparrow through the mead-hall,’ where the fire blazes, before flying out again into the winter. Of what lies before and ahead, we are utterly ignorant, said Bede. But now we look at a future that we have already predetermined by our own actions.

It is a tragedy for the planet’s wild creatures if they disappear: it is also a tragedy for us. If we lose all but our most domesticated companions, do we risk becoming something less than the humans we once were? Can we bear to live with just ourselves? Another way the Anthropocene era has been defined (by anthropologist Anna Tsing) is as an era without places of refuge for animals or people. ‘What, are all the green fields gone?’ asks Ishmael, hero of Melville’s Moby Dick, tired of humanity and tired of himself in a busy New York City; and so he takes himself and his ‘hypos’ to sea, into an immensity of ocean populated by great whales. No longer. As Mooallem writes, wildlife has always been ‘a reminder of all the mystery that exists outside my own experience.’ What happens once we lose all these great wonders? If we can’t value everything, Mooallem asks, can we value anything at all?

Yet even if we try to be good citizens, to protect those last animal refugees from a once-abundant age, the responsibility is terrifying. In 2004, I heard the conservationist Willie Smits speak at the Australian Museum in Sydney, and subequently hoped to write about him. A Dutchman who has made his life in Indonesia since 1985, Smits works with orangutans, which he described in his talk as being ‘like us, but more peaceful’. Founding the Borneo Orangutan Society in 1991 to rescue and protect trafficked orangutans, Smits created the Wanariset research station as a temporary refuge from which rehabilitated orangutans could be released back into the wild. But in 2001, as Indonesian deforestation continued at a terrifying pace, the charity bought 2000 acres of degraded rainforest Kalimantan and set about replanting it as a more permanent home. (Smits has claimed, controversially, that his accelerated reforestation has established its own cloud-attracting microclimate, which has increased rainfall in the local area by 25 per cent). Because orangutans in the wild usually stay with their mothers until they are around ten years of age, Smits also had to set up ‘forest schools’, in which human ‘teachers’ could train baby orangutans with the knowledge to survive. (And while the rehabilitated orangutans roam freely, most return to cages to sleep at night). But the work did not stop there. Smits had to build special islands in the middle of the river for those orangutans that had acquired human diseases or were disabled by maltreatment. To provide locals with income from the work of preservation, he planted a hundred-metre-wide ring of sugar palms around the sanctuary. He used satellite imagery to report palm oil companies breaking their permits to covertly clear-cut virgin forests and Google Earth to encourage donors to ‘adopt’ (and monitor) hectares of the sanctuary. More recently, he has even founded a factory to process sugar palm into sugar and ethanol, to pump cash and energy back into the local community and save 200,000 trees each year being cut for fuel wood. I admire Smits’s passion and yet as a writer I am fascinated by the terrible authority he has had to take on: hasn’t he had to become, in a sense, a kind of God, responsible for reimaging every element of this small new world?

This grim state of affairs—this ghastly closeness between the last wild creatures and human beings—seems to have been foretold by one of my favourite writers, Franz Kafka, in his tiny story, ‘A Crossbreed’ (subtitle: ‘A Sport’). In the space of a single page an unnamed man tells us that he has inherited a strange creature, half-lamb and half-kitten, from his father: it is unique, the only one of its kind. When it is pressed against him, the man says, it is happiest. When he cries, the animal seems to cry too; when it peers into his face and he pretends to understand it, it capers with joy to the point where he is forced to wonder if it ‘has the ambitions of a human being’. And yet, the narrator also finds himself convinced that the creature wants to die; that the butcher’s knife might be a ‘relief’. Sometimes, the narrator concludes, it ‘gazes at me with a look of human understanding, challenging me to do the thing of which both of us are thinking.’ I read this as a dire parable of animals’ fate, and ours, at the end of nature: a kind of endgame (as the subtitle suggests) of false closeness, in which we cannot live with, or without, each other.

At the same time as humans like Smits are trying to replicate the parts of the broken web of nature, scientists have been discovering it is far more complex than we thought. We are starting to understand the bioluminescence of sea creatures as a sophisticated language; we are being told, in books like The Hidden Life of Trees, about the extraordinary levels of communication between trees via their intertwined root systems: that living trees feed sugars to sick trees and even to deadwood on the ground; that ‘mother’ trees protect their ‘children’. What this makes clear is that our idea of nature’s abundance was faulty in the first place. We have more often treated plenitude as an invitation to plunder than to be in touch with awe or wonder. Yet the Gadigal middens remind us that things have never really been ripe for the taking. The fact is that you can’t ‘just’ take the giant cedars from a rainforest without wildly altering that small ecology; you can’t cull elephants from a herd without damaging a sophisticated culture (in Africa, scientists have observed angry adolescent elephants terrorizing other animals in the Kruger National Park because rangers, in attempts to ‘thin’ the population, have removed the dominant bulls). So I realise now that my longing for books about nature’s past profusion may be part of the problem.

But what can writers do, faced with a world whose abundance, in the fuller sense of frail complexity, is vanishing before our eyes? Apart from the question of whether art can have much real effect against the overwhelming threats we (humans and other living beings) face, it’s possible that the underpinnings of storytelling itself may be endangered. The passage of the seasons; the opposition between wild and domestic; the ideal of progress; and even the notion of futurity—all these drivers of the writerly machinery—now seem hollow. It is increasingly hard to believe in that magic transaction scholar Robert Pogue Harrison describes in which the dead speak to future generations, which literature constantly enacts. Apart from the moral anguish and grief our diminishing biosphere creates, philosopher Freya Mathews suggests, the story of the earth—the story of its ‘symphonic synergies’ in which its parts renew each other, in which everything conspires with everything else to bring forth new life (where even death is converted back into life)— is itself on the edge of unravelling. This proto-story is the primal template for meaning: without it, ‘everything is in jeopardy’.

Of course, as a writer, trying to work out how to write — or in fact, whether to write at all — I have not just been hunkered in the bathtub with the books of last century. I have been reading more broadly; and it strikes me that writers, of both fiction and nonfiction, are practically turning themselves inside out trying to grapple with these questions. In the first rank are books like journalist Elizabeth Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction, which try to simply tell the story of this loss, stringing together local instances in ways that might let us grasp the bigger picture. Others, like Michael McCarthy’s The Moth Snowstorm, are using autobiography to look back at the loss of abundance and question what it means. McCarthy, a nature writer, begins his account of the ‘great thinning’ of British wildlife by invoking the storms of moths in the car headlights when the was a child in the 1950s — now long gone — while his book hovers between trying to take joy in those wonders of nature that are left and defending nature as something that ‘looks outwards, to another purpose, another power’.

Other nature writers been reworking the genre of nature writing to make it uncomfortable. In Orison for a Curlew, English writer Horatio Clare, travels the world in search of the slender-billed curlew — a plentiful wonder of his childhood — and finds none; the story is a pilgrimage of hope, but ultimately, loss. In Moby-Duck, a personal favourite, Donovan Hohn transforms the expected hunt for a living creature into a quest to find a legendary shipping container of rubber ducks that fell into the ocean, a mission that takes him on a journey through changing ocean currents and the Great North Pacific Garbage Patch.

Another group of authors is looking ahead. For Roy Scranton, an ex-US soldier who faced death in Iraq, it’s only acceptance of the catastrophe to come that will enable us to salvage anything. ‘The biggest problem we face now,’ he writes in Learning to Die in the Anthropocene, ‘is a philosophical one: understanding that this civilization is already dead. The sooner we confront this problem, and the sooner we realize there is nothing we can do to save ourselves, the sooner we can get down to the hard work of adapting, with mortal humility, to our new reality.’ Some novelists plunge into the disasters ahead (we tend to lazily classify such dystopian books as ‘cli fi’) while others try to offer a thread of hope within that future, not as solace but as incentive. In his novel Clade, James Bradley follows ten generations from the present into the future. It is a terribly sad novel, but one also marked by its author and characters’ ability to persevere and to hold onto their human capacity to form bonds and see beauty — because to accept only the numbing fantasy of apocalypse, Bradley has said in interviews, is to give up.

Then there are novels that bring human and nonhuman more closely together to insist on our interconnection — which means accepting very profound changes to our expectations of narrative and character. One such novel is British author Jon McGregor’s distinctly odd Reservoir 13, an imploded mystery story published just this year. Over a ten-year span, the novel tracks the effects of a teenage girl’s unsolved disappearance on a small town in the north of England: a town, we are constantly reminded, where thirteen man-made reservoirs perch precariously in the high country above it. While the various human characters go about their business, so, most unusually, do the animals—often in the same paragraph. As a woman winds her twin babies’ mobiles, badgers in the beech wood feed quickly, ‘laying down fat for the winter ahead’, while the river runs towards the millpond weir. (There is, incidentally, an equivalent in nonfiction: eco-biography, which looks at human lives within the bigger story of the natural world).

In How the Dead Dream, American writer Lydia Millet takes the Bildungsroman and turns it back on itself. ‘T’, a young property developer in Los Angeles, is on a relentless trajectory to success when, more than halfway through the novel, he becomes obsessed by animals on the verge of extinction and starts to break into zoos to observe them. As events beyond his control begin to bring his biography into parallel with theirs, his loneliness delivers the radical intuition that nature is already almost dead. More than that: he begins to feel that these captives also experience an existential melancholy equivalent to solastalgia:

It was obvious: all of them waited and they waited, up until their last day and their last night of sleep. They never gave up waiting, because they had nothing else to do. They waited to go back to the bright land; they wanted to go home.’

Meanwhile, in The Great Derangement, published this year, Amitav Ghosh has called on novelists to divest from the realist novel because it has been in the business too long of maintaining a bourgeois order that ‘conceals’ the ongoing plight of the world. To maintain a smooth surface, the realist novel tends to frame extreme events as extraordinary: too many extreme events in the one book will demote a novel to the lower realms of sensationalist fiction. But if the extraordinary is our new ordinary, he writes, shouldn’t novelists of ‘serious fiction’ give up on an aesthetic commitment to banishing the improbable and start depicting climate change explicitly?

Ghosh pits the literary novel—narrowly defined—against ‘genre’, defined narrowly again as cli-fi. Yet as James Bradley has pointed out, popular culture may have been well ahead of the game, as it so often is, in this regard. Is it any coincidence that our screens over the last decade have been so populated by the undead: by vampires and zombies? Twenty-first-century vampires are burdened by their knowledge of themselves as predators and by the dead weight of future time; aren’t they, in these ways, really us? Zombies are even more terrifying avatars for humanity in the age of extinction. To be a zombie is to be reduced to having no story at all, and no mission or sense of the future, except to consume the living. If we are coming to the end of our stories in the Age of Loneliness, as Freya Mathews fears, there is perhaps no more apt metaphor than the zombie of an already-dead humanity feeding on itself.

And yet I must admit, as I have thought hard lately about the role of writing, it has been with a certain despair. Literature is a niche interest these days, and no matter how hard one might work as an author to accept change or stave off disaster, it seems that writing is over ‘here’ – and that there is a far more powerful, dominant narrative version of the world over ‘there’, which I think of as the narrative of glamour. The fact is that for every book concerned with the fate of the world, there are a hundred, a thousand, films and books and ‘lifestyle’ television programs and advertisements and magazines offering an alternate universe that is already here on earth. Glamour exists on a different time scale where nothing is permanent but can always be ‘made over’ — houses flipped, dream homes located, ugly ducklings zhoozhed. In its alternate universe decisions are not moral, but only ever aesthetic, surfaces always gleam, and those who have glamour are ‘winners’ — above the ruck, in their gilded sphere — while those who don’t are ‘losers’. If social realist fiction is the Trojan horse of the bourgeois order, as Ghosh claims, then glamour is the great enabler of a neoliberal logic, hiding its longterm and catastrophic damage with a glossy fluidity.

Glamour may be our most powerful and fatal fiction, the one that kills us all. I find myself thinking back to True Blood, one of those vampire-themed shows of the last decade, in which to ‘glamour’ someone—drawing on the old Scottish sense of the verb—is to hypnotise them or bend them to your will. For all the commentary on the US election, I’ve not seen much about Trump as a conduit for glamour-as-magical-thinking — albeit a debased version, of Mar-a-Lago resorts and $22 Platinum Label Burgers (Proprietary Blend of Prime aged short rib, caramelized onions, Tarentaise cheese, horseradish, aioli, brioche roll) at the Trump Grill. Trump has brought into politics the faux glamour of a television show about entrepreneurialism, but he is only the most egregious embodiment of the logic of ‘makeover’, which offers itself as an alternative to the longer historical claims of climate doomsayers. The logic extends itself, less obviously, into surprising spaces: in our town planning, for example, where spaces are no longer valued for their local histories, but endlessly ‘activated’. I can’t help wondering, as I pass the newest temporary sculpture or pop-up in my own neighbourhood: is this fervent lip-service to endlessly plastic places merely softening us up for the great unravelling under way?

And so I find myself disagreeing with Ghosh. In contrast to his negative view of realism, I think there is still an urgent need for fiction that can register the tiny cultural shifts that are enabling the disaster that is unfolding everywhere around us, at least resisting glamour by capturing how it works in the here and now. Historical fiction, too, has its mission: to register the longer time-frames that disturb an anaesthetised present and work against generational amnesia. (For this reason, I experience intense unease reading novels that shift the parameters of history—like Sarah Perry’s Essex Serpent, with its disconcertingly modern characters—because I’m not sure that they don’t extend the glamour’s reign into the past). I’d also observe that we writers also need to resist being glamoured ourselves. I’ve started to notice, over the last few years, an evangelical tone creeping into writers’ festivals, in which writers proselytise the power of literature to ‘represent complexity’ or make us better people. As writers are encouraged to promote ourselves as brands, it’s too easy to pat ourselves on the back for simply writing, rather than worrying about the specific work our books can do in the world. I suspect that we’re much better off conceding that writing doesn’t have much power and then seeing what we can do.

It is a tiny consolation that Australia may be the best place for writing about uncertainty and loss. Our colonial history means that our literature is already less comfortable than its northern hemisphere counterparts and more tuned to damage and survival. This is especially the case in writing about nature, which has never established itself as a stable commercial genre here but tends instead to emerge in feral form out of other genres, such as history and memoir. It almost always engages with the ongoing Indigenous knowledge of country. Books such as Bruce Pascoe’s galvanising Dark Emu, Kim Mahood’s Position Doubtful and Saskia Beudel’s walking memoir, A Country in Mind, are sceptical of any Romantic sense of boundless plenty and adept, in their different ways, at negotiating the rough terrain of broken country; none could be described as “nature writing” but each is tuned, as Beudel puts it beautifully, to the ‘off-key tone of colonised land’. One of the great strengths of such recent Australian writing is that it is never just about the present, but works its way back into the past to make us think hard about what we think we already know; and it gives us a more complex set of tools to think about the future. Reading Pascoe’s galvanizing book, in which he digs back into the colonial records to reveal an obscured history of Aboriginal farming and building, is to experience a fantastic kind of double vision, in which he re-sees the damaged land, in terms of what is lost but also what continues. If we are going to face up to the terrible choices ahead, Australian writing, with its self-consciousness, sometimes awkward manners, and unsentimental sense of complexity—all, significantly, the opposite of glamour—may offer the best way forward. Its wise sense of abundance as historical, layered, contingent and mutable, is a better place, at least, to start.

This is an edited version of the inaugural Eleanor Dark Lecture, delivered by Delia Falconer in Katoomba at the Varuna Sydney Writers Festival on 29 May 2017.

Works Cited

John Berger, ‘Why Look at Animals?’ from About Looking (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980).

James Bradley, Clade (Melbourne: Hamish Hamilton, 2015).

Saskia Beudel, A Country in Mind: Memoir with Landscape (Crawley, University of Western Australia Publishing, 2013).

Horatio Clare, Orison for a Curlew (Wimborne Minster: Little Toller Books, 2016).

Delia Falconer, Sydney (Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2010).

Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

Donovan Hohn, Moby-Duck: The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists, and Fools, Including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them (New York: Penguin Putnam Inc, 2012).

Franz Kafka, ‘A Cross-Breed (A Sport)’, from The Penguin Complete Stories of Franz Kafka, Nahum N. Glatzer, Ed. (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983).

Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2014).

Robert Pogue Harrison, The Dominion of the Dead (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

Kim Mahood, Position Doubtful: Mapping Landscapes and Memories (Brunswick: Scribe, 2016).

Freya Mathews, ‘Planet Beehive,’ Australian Humanities Review Issue 50, May 2011.

Michael McCarthy, The Moth Snowstorm: Nature and Joy (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2016).

Jon McGregor, Reservoir 13 (London: HarperCollins, 2017).

Herman Melville, Moby Dick; or, The White Whale (London: Dent, 1907).

Lydia Millet, How the Dead Dream (Boston: Mariner Books, 2009).

Jon Mooallem, Wild Ones: A Sometimes Dismaying, Weirdly Reassuring Story about Looking at People Looking at Animals in America (London: The Penguin Press, 2013).

Les Murray, ‘The Flying-Fox Dreaming’ from The New Collected Poems (Sydney: Duffy & Snellgrove, 2002).

Bruce Pascoe, Dark Emu: Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident? (Broome, Magabala Books, 2014).

Sarah Perry, The Essex Serpent (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2017).

Roy Scranton, Learning to Die in the Anthropocene: Reflections on the End of a Civilization (Oregon: City Lights Books, 2015).

John Steinbeck, The Log from the Sea of Cortez (London: PanBooks, 1960).

– Cannery Row (London: Penguin Classics, 1994).

Peter Wohlleben, The Hidden Life of Trees (Melbourne: Black Inc, 2016).