This article originally appeared in the December 1972 issue of Esquire. To read every Esquire story ever published, upgrade to All Access.

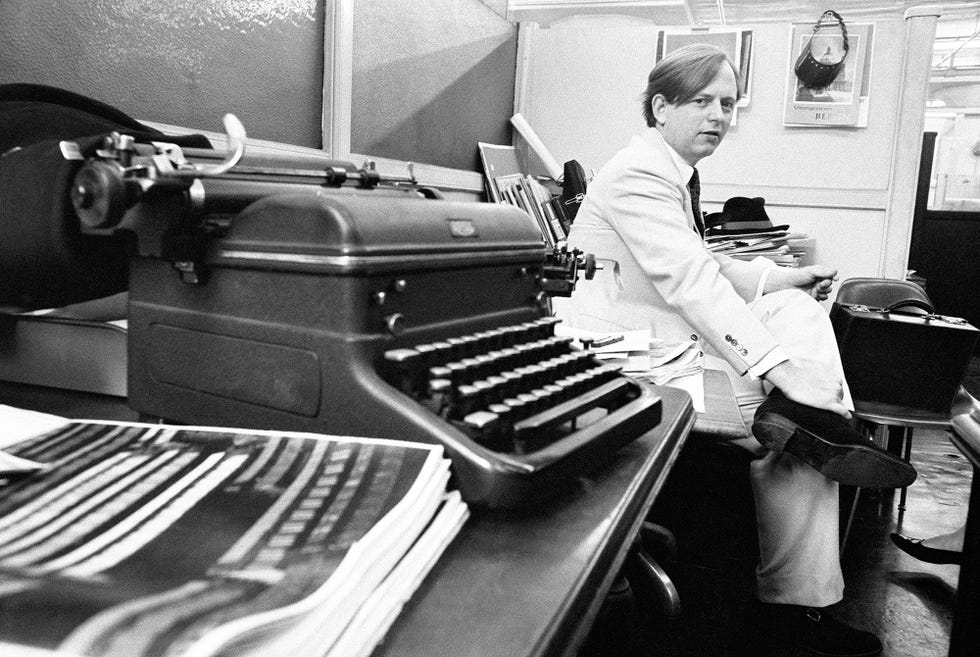

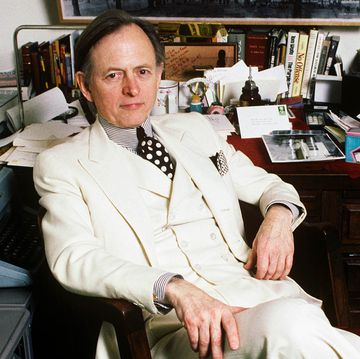

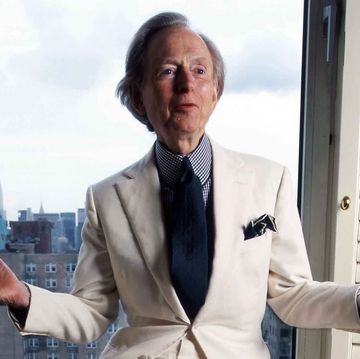

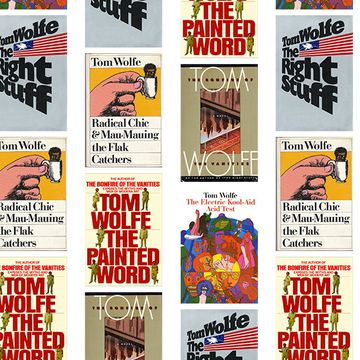

I have no idea who coined the term “the New Journalism” or even when it was coined. Seymour Krim tells me that he first heard it used in 1965 when he was editor of Nugget and Pete Hamill called him and said he wanted to write an article called “The New Journalism” about people like Jimmy Breslin and Gay Talese. It was late in 1966 when you first started hearing people talk about “the New Journalism” in conversation, as best I can remember. I don’t know for sure.... To tell the truth, I’ve never even liked the term. Any movement, group, party, program, philosophy or theory that goes under a name with “New” in it is just begging for trouble. The garbage barge of history is already full of them: the New Humanism, the New Poetry, the New Criticism, the New Conservativism, the New Frontier, il Stilo Novo ... The World Tomorrow.... Nevertheless, the New Journalism was the term that caught on eventually. At the time, the mid-Sixties, one was aware only that all of a sudden there was some sort of artistic excitement in journalism, and that was a new thing in itself.

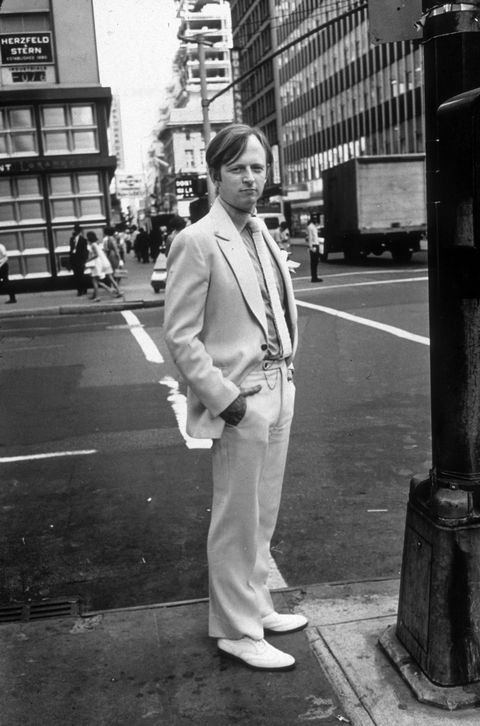

I didn’t know what history, if any, lay behind it. I wasn’t interested in the long view just then. All I knew was what certain writers were doing at Esquire, Thomas B. Morgan, Brock Brower, Terry Southern and, above all, Gay Talese ... even a couple of novelists were in on it, Norman Mailer and James Baldwin, writing nonfiction for Esquire ... and, of course, the writers for my own Sunday supplement, New York, chiefly Breslin, but also Robert Christgau, Doon Arbus, Gail Sheehy, Tom Gallagher, Robert Benton and David Newman. I was turning out articles as fast as I could write and checking out all these people to see what new spins they had come up with. I was completely wrapped up in this new excitement that was in the air. It was a regular little league we had going.

As a result I never had the slightest idea that what we were doing might have an impact on the literary world or, for that matter, any sphere outside the small world of feature journalism. I should have known better, however. By 1966 we had already been paid literary tribute in its cash forms: namely, bitterness, envy and resentment.

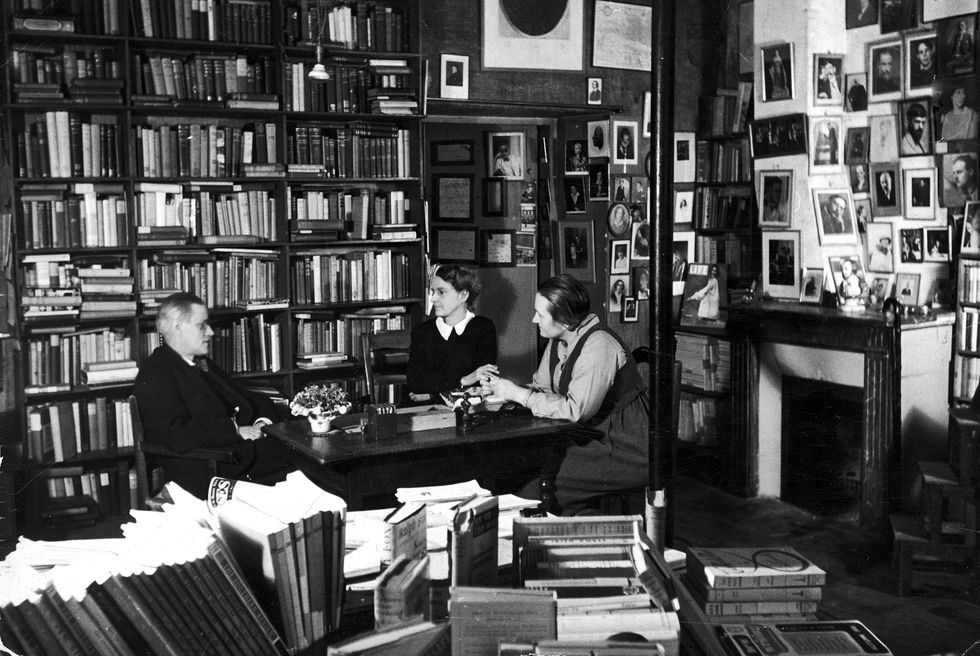

This had all come bursting forth during a curious episode known as The New Yorker affair. In April of 1965, in the New York Herald Tribune’s Sunday magazine, New York, I had made what I fancied was some lighthearted fun of The New Yorker magazine with a two-part article entitled “Tiny Mummies! The True Story of the Ruler of 43rd Street’s Land of The Walking Dead!” A very droll sportif performance, you understand. Without going into the whole beanball contest I can tell you that there were many good souls who did not consider this article either lighthearted or sportif. In fact, it caused a hulking furor. In the midst of it the Kentucky colonels of both Journalism and Literature launched their first attack on this accursed Low Rent rabble at the door, these magazine writers working in the damnable new form….

The longest attacks came in two fairly new but highly conservative periodicals. One was mounted by what had already become the major organ of traditional newspaper journalism in the United States, the Columbia Journalism Review, and the other by the major organ of America’s older literary essayists and “men of letters,” The New York Review of Books. They presented lists of “errors” in my piece about The New Yorker, marvelous lists [1] as arcane and mystifying as a bill from the body shop—whereupon they concluded that there you had the damnable new genre, this “bastard form,” this “Parajournalism,” a tag they awarded not only to me and to my magazine New York and all its works but also to Breslin, Talese, Dick Schaap and, as long as they were up, Esquire [2]. Whether or not one accepted the lists, the strategy itself was revealing. My article on The New Yorker had not even been an example of the new genre; it used neither the reporting techniques nor the literary techniques; underneath a bit of red-flock Police Gazette rhetoric, it was a traditional critique, a needle, an attack, an “essay” of the old school. It had little or nothing to do with anything I had written before. It certainly had nothing to do with any other writer’s work. And yet I think the journalists and literati who were so furious were sincere. I think they looked at the work a dozen or so writers, Breslin, Talese and myself among them, were doing for New York and Esquire, and they were baffled, dazzled.... They had just about the same instinctive, defensive reaction I had had three years before when I read a remarkable piece by Gay Talese about Joe Louis.... This can’t be right.... These people must be piping it, winging it, making up the dialogue.... Christ, maybe they’re making up whole scenes, the unscrupulous geeks (I’m telling you, Ump, those are spitballs they’re throwing). They needed to believe, in short, that the new form was illegitimate ... a “bastard form.”

Why newspaper people were upset was no mystery. They were better than railroad men at resisting anything labeled new. The average newspaper editor’s idea of a major innovation was the Cashword Puzzle. The literary opposition was more complex, however. Looking back on it one can see that what had happened was this: the sudden arrival of this new style of journalism, from out of nowhere, had caused a status panic in the literary community. Throughout the twentieth century literary people had grown used to a very stable and apparently eternal status structure. It was somewhat like a class structure on the eighteenth-century model in that there was a chance for you to compete but only with people of your own class. The literary upper class were the novelists; the occasional playwright or poet might be up there, too, but mainly it was the novelists. They were regarded as the only “creative” writers, the only literary artists. They had exclusive entry to the soul of man, the profound emotions, the eternal mysteries, and so forth and so on.... The middle class were the “men of letters,” the literary essayists, the more authoritative critics; the occasional biographer, historian or cosmically inclined scientist also, but mainly the men of letters. Their province was analysis, “insights,” the play of intellect. They were not in the same class with the novelists, as they well knew, but they were the reigning practitioners of nonfiction.... The lower class were the journalists, and they were so low down in the structure that they were barely noticed at all. They were regarded chiefly as day laborers who dug up slags of raw information for writers of higher “sensibility” to make better use of. As for people who wrote for popular (“slick”) magazines and Sunday supplements, your so-called free-lance writers—except for a few people on The New Yorker, they weren’t even in the game. They were the lumpenproles.

And so all of a sudden, in the mid-Sixties, here comes a bunch of these lumpenproles, no less, a bunch of slick-magazine and Sunday-supplement writers with no literary credentials whatsoever in most cases—only they’re using all the techniques of the novelists, even the most sophisticated ones—and on top of that they’re helping themselves to the insights of the men of letters while they’re at it—and at the same time they’re still doing their low-life legwork, their “digging,” their hustling, their damnable Locker Room Genre reporting—they’re taking on all of these roles at the same time—in other words, they’re ignoring literary class lines that have been almost a century in the making.

Read more iconic Esquire stories on Esquire Classic.

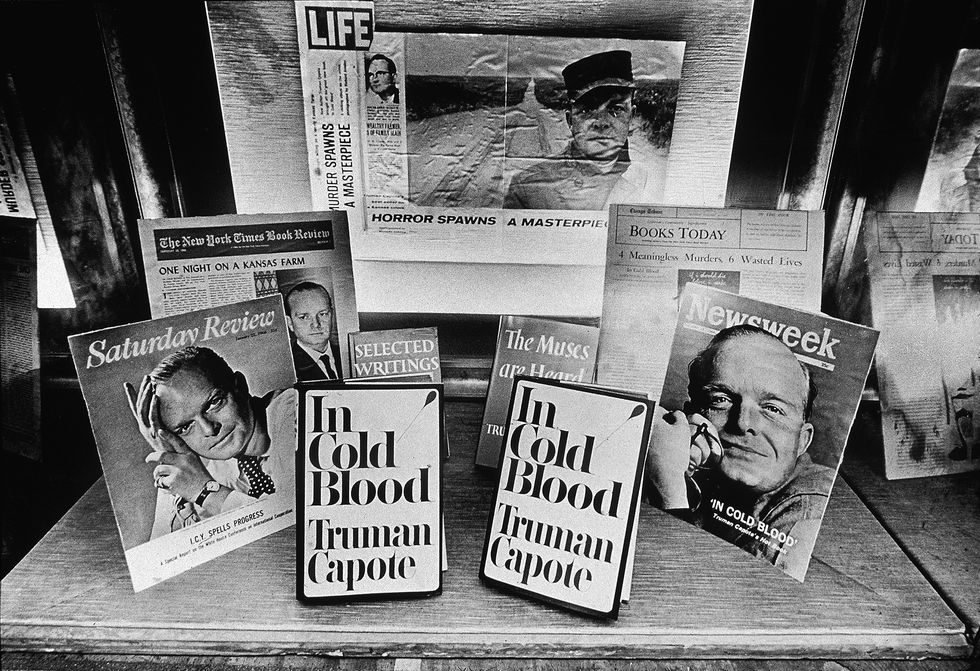

The panic hit the men of letters first. If the lumpenproles won their point, if their new form achieved any sort of literary respectability, if it were somehow accepted as “creative,” the men of letters stood to lose even their positions as the reigning practitioners of nonfiction. They would get bumped down to Lower Middle Class. This was already beginning to happen. The first indication I had came in an article in the June, 1966, Atlantic by Dan Wakefield, entitled “The Personal Voice and the Impersonal Eye.” The gist of the piece was that this was the first period in anybody’s memory when people in the literary world were beginning to talk about nonfiction as a serious artistic form. Norman Podhoretz had written a piece in Harper’s in 1958 claiming a similar status for the “discursive prose” of the late Fifties, essays by people like James Baldwin and Isaac Rosenfeld. But the excitement Wakefield was talking about had nothing to do with essays or any other traditional nonfiction. Quite the contrary; Wakefield attributed the new prestige of nonfiction to two books of an entirely different sort: In Cold Blood, by Truman Capote, and a collection of magazine articles with a title in alliterative trochaic pentameter that I am sure would come to me if I dwelled upon it.

Capote’s story of the life and death of two drifters who blew the heads off a wealthy farm family in Kansas ran as a serial in The New Yorker in the Fall of 1965 and came out in book form in February of 1966. It was a sensation—and a terrible jolt to all who expected the accursed New Journalism or Parajournalism to spin itself out like a fad. Here, after all, was not some obscure journalist, some free-lance writer, but a novelist of long standing ... whose career had been in the doldrums ... and who suddenly, with this one stroke, with this turn to the damnable new form of journalism, not only resuscitated his reputation but elevated it higher than ever before ... and became a celebrity of the most amazing magnitude in the bargain. People of all sorts read In Cold Blood, people at every level of taste. Everybody was absorbed in it. Capote himself didn’t call it journalism; far from it; he said he had invented a new literary genre, “the nonfiction novel.” Nevertheless, his success gave the New Journalism, as it would soon be called, an overwhelming momentum.

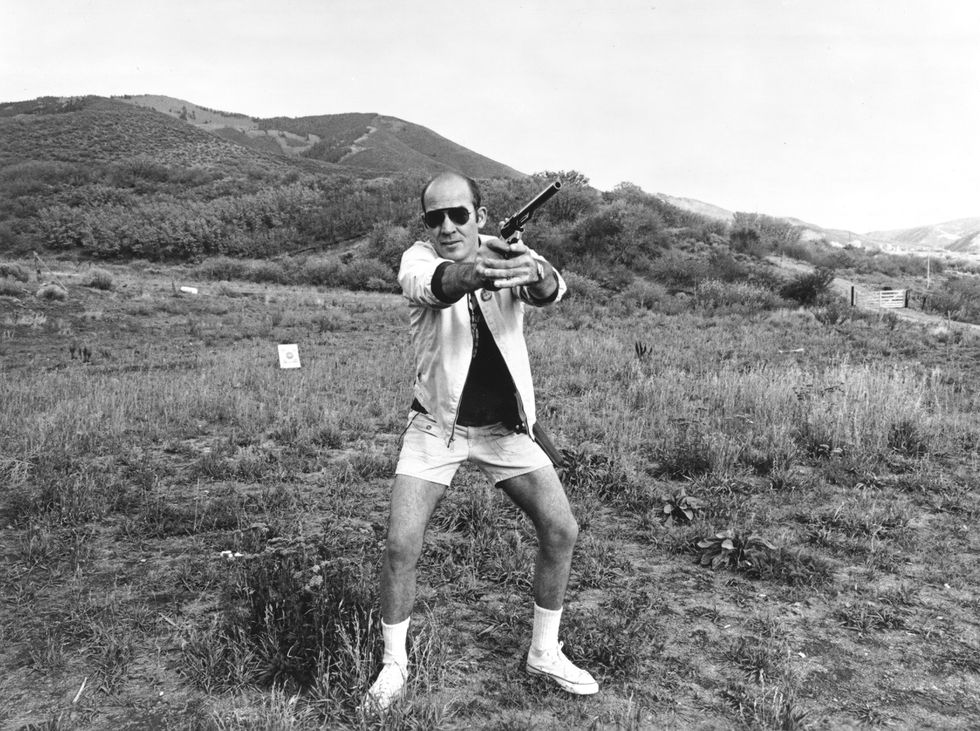

Capote had spent five years researching his story and interviewing the killers in prison, and so on, a very meticulous and impressive job. But in 1966 you started seeing feats of reporting that were extraordinary, spectacular. Here came a breed of journalists who somehow had the moxie to talk their way inside of any milieu, even closed societies, and hang on for dear life. A marvelous maniac named John Sack talked the Army into letting him join an infantry company at Fort Dix, M Company, 1st Advanced Infantry Training Brigade—not as a recruit but as a reporter—and go through training with them and then to Vietnam and into battle. The result was a book called M (appearing first in Esquire), a nonfiction Catch-22 and, for my money, still the finest book in any genre published about the war. George Plimpton went into training with a professional football team, the Detroit Lions, in the role of reporter playing rookie quarterback, rooming with the players, going through their workouts and finally playing quarterback for them in a preseason game—in order to write Paper Lion. Like Capote’s book, Paper Lion was read by people at every level of taste and had perhaps the greatest literary impact of any writing about sports since Ring Lardner’s short stories. But the all-time free-lance writer’s Brass Stud Award went that year to an obscure California journalist named Hunter Thompson who “ran” with the Hell’s Angels for eighteen months—as a reporter and not a member, which might have been safer—in order to write Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gang. The Angels wrote his last chapter for him by stomping him half to death in a roadhouse fifty miles from Santa Rosa. All through the book Thompson had been searching for the single psychological or sociological insight that would sum up all he had seen, the single golden aperçu; and as he lay sprawled there on the floor coughing up blood and teeth, the line he had been looking for came to him in a brilliant flash from out of the heart of darkness: “Exterminate all the brutes!”

At about the same time, 1966 and 1967, Joan Didion was writing those strange Gothic articles of hers about California that were eventually collected in Slouching Towards Bethlehem. Rex Reed was writing his celebrity interviews—this was an old journalistic exercise, of course, but no one had ever quite so diligently addressed himself to the question of, “What is So-and-so really like?” (Simone Signoret, as I recall, turned out to have the neck, shoulders and upper back of a middle linebacker.) James Mills was pulling off some amazing reporting feats of his own for Life in pieces such as “The Panic in Needle Park,” “The Detective,” and “The Prosecutor.” The writer-reporter team of Garry Wills and Ovid Demaris was doing a series of brilliant pieces for Esquire, culminating in “You All Know Me—I’m Jack Ruby!”

And then, early in 1968, another novelist turned to nonfiction, and with a success that in its own way was as spectacular as Capote’s two years before. This was Norman Mailer writing a memoir about an antiwar demonstration he had become involved in, “The Steps of the Pentagon.” The memoir, or autobiography, is an old genre of nonfiction, of course, but this piece was written soon enough after the event to have a journalistic impact. It took up an entire issue of Harper’s Magazine and came out a few months later under the title of The Armies Of The Night. Unlike Capote’s book, Mailer’s was not a popular success; but within the literary community and among intellectuals generally it couldn’t have been a more tremendous succès d’estime. At the time Mailer’s reputation had been deteriorating in the wake of two inept novels called An American Dream (1965) and Why Are We In Vietnam? (1967). He was being categorized somewhat condescendingly as a journalist, because his nonfiction, chiefly in Esquire, was obviously his better work. The Armies Of The Night changed all that in a flash. Like Capote, Mailer had a dread of the tag that had been put on him—“journalist”—and had subtitled his book “The Novel as History; History as the Novel.” But the lesson was one that nobody in the literary world could miss. Here was another novelist who had turned to some form of accursed journalism, no matter what name you gave it, and had not only revived his reputation but raised it to a point higher than it had ever been in his life.

By 1969 no one in the literary world could simply dismiss this new journalism as an inferior genre. The situation was somewhat similar to the situation of the novel in England in the 1850’s. It was yet to be canonized, sanctified and given a theology, but writers themselves could already feel the new Power flowing.

The similarity between the early days of the novel and the early days of the New Journalism is not merely coincidental. In both cases we are watching the same process. We are watching a group of writers coming along, working in a genre regarded as Lower Class (the novel before the 1850’s, slick-magazine journalism before the 1960’s), who discover the joys of detailed realism and its strange powers. Many of them seem to be in love with realism for its own sake; and never mind the “sacred callings” of literature. They seem to be saying: “Hey! Come here! This is the way people are living now—just the way I’m going to show you! It may astound you, disgust you, delight you or arouse your contempt or make you laugh.... Nevertheless, this is what it’s like! It’s all right here! You won’t be bored! Take a look!”

As I hardly have to tell you, that is not exactly the way serious novelists regard the task of the novel today. In this decade, the Seventies, The Novel will be celebrating the one-hundredth anniversary of its canonization as the spiritual genre. Novelists today keep using words like “myth,” “fable” and “magic.” That state of mind known as “the sacred office of the novelist” had originated in Europe in the 1870’s and didn’t take hold in the American literary world until after the Second World War. But it soon made up for lost time. What kind of novel should a sacred officer write? In 1948 Lionel Trilling presented the theory that the novel of social realism (which had flourished in America throughout the 1930’s) was finished because the freight train of history had passed it by. The argument was that such novels were a product of the rise of the bourgeoisie in the nineteenth century at the height of capitalism. But now bourgeois society was breaking up, fragmenting. A novelist could no longer portray a part of that society and hope to capture the Zeitgeist; all he would be left with was one of the broken pieces. The only hope was a new kind of novel (his candidate was the novel of ideas). This theory caught on among young novelists with an astonishing grip. Whole careers were altered. All those writers hanging out in the literary pubs in New York such as the White Horse Tavern rushed off to write every kind of novel you could imagine, so long as it wasn’t the so-called “big novel” of manners and society. The next thing one knew, they were into novels of ideas, Freudian novels, surrealistic novels (“black comedy”), Kafkaesque novels and, more recently, the catatonic novel or novel of immobility, the sort that begins: “In order to get started, he went to live alone on an island and shot himself.” (Opening line of a Robert Coover short story.)

As a result, by the Sixties, about the time I came to New York, the most serious, ambitious and, presumably, talented novelists had abandoned the richest terrain of the novel: namely, society, the social tableau, manners and morals, the whole business of “the way we live now,” in Trollope’s phrase. There is no novelist who will be remembered as the novelist who captured the Sixties in America, or even in New York, in the sense that Thackeray was the chronicler of London in the 1840’s and Balzac was the chronicler of Paris and all of France after the fall of the Empire. Balzac prided himself on being “the secretary of French society.” Most serious American novelists would rather cut their wrists than be known as “the secretary of American society,” and not merely because of ideological considerations. With fable, myth and the sacred office to think about—who wants such a menial role?

That was marvelous for journalists—I can tell you that. The Sixties was one of the most extraordinary decades in American history in terms of manners and morals. Manners and morals were the history of the Sixties. A hundred years from now when historians write about the 1960’s in America (always assuming, to paraphrase Céline, that the Chinese will still give a damn about American history), they won’t write about it as the decade of the war in Vietnam or of space exploration or of political assassinations ... but as the decade when manners and morals, styles of living, attitudes toward the world changed the country more crucially than any political events ... all the changes that were labeled, however clumsily, with such tags as “the generation gap,” “the counter culture,” “black consciousness,” “sexual permissiveness,” “the death of God,” ... the abandonment of proprieties, pieties, decorums connoted by “go-go funds,” “fast money,” swinger groovy hippie drop-out pop Beatles Andy Baby Jane Bernie Huey Eldridge LSD marathon encounter stone underground rip-off.... This whole side of American life that gushed forth when postwar American affluence finally blew the lid off—all this novelists turned away from, gave up by default. That left a huge gap in American letters, a gap big enough to drive an ungainly Reo rig like the New Journalism through.

When I reached New York in the early Sixties, I couldn’t believe the scene I saw spread out before me. New York was pandemonium with a big grin on. Among people with money—and they seemed to be multiplying like shad—it was the wildest, looniest time since the 1920’s ... a universe of creamy forty-five-year-old fashionable fatties with walnut-shell eyes out on the giblet slab wearing the hip-huggers and the minis and the Little Egypt eyes and the sideburns and the boots and the bells and the love beads, doing the Watusi and the Funky Broadway and jiggling and grinning and sweating and sweating and grinning and jiggling until the onset of dawn or saline depletion, whichever came first.... It was a hulking carnival. But what really amazed me was that as a writer I had it practically all to myself. As fast as I could possibly do it, I was turning out articles on this amazing spectacle that I saw bubbling and screaming right there in front of my wondering eyes—New York!—and all the while I just knew that some enterprising novelist was going to come along and do this whole marvelous scene with one gigantic daring bold stroke. It was so ready, so ripe—beckoning ... but it never happened. To my great amazement New York simply remained the journalist’s bonanza. For that matter, novelists seemed to shy away from the life of the great cities altogether. The thought of tackling such a subject seemed to terrify them, confuse them, make them doubt their own powers. And besides, it would have meant tackling social realism as well.

To my even greater amazement I had the same experience when I came upon 1960’s California. This was the very incubator of new styles of living, and these styles were right there for all to see, ricocheting off every eyeball—and again we—a few journalists working in the new form—had it all to ourselves, even the psychedelic movement, whose waves are still felt in every part of the country, in every grammar school even, like the intergalactic pulse. I wrote The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test and then waited for the novels that I was sure would come pouring out of the psychedelic experience ... but they never came forth, either. I learned later that publishers had been waiting, too. They had been practically crying for novels by the new writers who must be out there somewhere, the new writers who would do the big novels of the hippie life or campus life or radical movements or the war in Vietnam or dope or sex or black militancy or encounter groups or the whole whirlpool all at once. They waited, and all they got was the Prince of Alienation ... sailing off to Lonesome Island on his Tarot boat with his back turned and his Timeless cape on, reeking of camphor balls.

Amazing, as I say. If nothing else had done it, that would have. We—New Journalists—Parajournalists—had the whole crazed obscene uproarious Mammon-faced drug-soaked mau-mau lust-oozing Sixties in America all to ourselves.

So the novelists had been kind enough to leave behind for our boys quite a nice little body of material: the whole of American society, in effect. It only remained to be seen if magazine writers could master the techniques, in nonfiction, that had given the novel of social realism such power. And here we come to a fine piece of irony. In abandoning social realism novelists also abandoned certain vital matters of technique. As a result, by 1969 it was obvious that these magazine writers—the very lumpenproles themselves!—had also gained a technical edge on novelists. It was marvelous. For journalists to take Technique away from the novelists—somehow it reminded me of Edmund Wilson’s old exhortation in the early 1930’s: Let’s take communism away from the Communists.

If you follow the progress of the New Journalism closely through the 1960’s, you see an interesting thing happening. You see journalists learning the techniques of realism—particularly of the sort found in Fielding, Smollett, Balzac, Dickens and Gogol—from scratch. By trial and error, by “instinct” rather than theory, journalists began to discover the devices that gave the realistic novel its unique power, variously known as its “immediacy,” its “concrete reality,” its “emotional involvement,” its “gripping” or “absorbing” quality.

This extraordinary power was derived mainly from just four devices, they discovered. The basic one was scene-by-scene construction, telling the story by moving from scene to scene and resorting as little as possible to sheer historical narrative. Hence the sometimes extraordinary feats of reporting that the new journalists undertook: so that they could actually witness the scenes in other people’s lives as they took place—and record the dialogue in full, which was device No. 2. Magazine writers, like the early novelists, learned by trial and error something that has since been demonstrated in academic studies: namely, that realistic dialogue involves the reader more completely than any other single device. It also establishes and defines character more quickly and effectively than any other single device. (Dickens has a way of fixing a character in your mind so that you have the feeling he has described every inch of his appearance—only to go back and discover that he actually took care of the physical description in two or three sentences; the rest he has accomplished with dialogue.) Journalists were working on dialogue of the fullest, most completely revealing sort in the very moment when novelists were cutting back, using dialogue in more and more cryptic, fey and curiously abstract ways.

The third device was the so-called “third-person point of view,” the technique of presenting every scene to the reader through the eyes of a particular character, giving the reader the feeling of being inside the character’s mind and experiencing the emotional reality of the scene as he experiences it. Journalists had often used the first-person point of view—“I was there”—just as autobiographers, memoirists and novelists had. This is very limiting for the journalist, however, since he can bring the reader inside the mind of only one character—himself—a point of view that often proves irrelevant to the story and irritating to the reader. Yet how could a journalist, writing nonfiction, accurately penetrate the thoughts of another person?

The answer proved to be marvelously simple: interview him about his thoughts and emotions, along with everything else. This was what Gay Talese did in order to write Honor Thy Father. In M, John Sack had gone a step further and used both third-person point of view and the interior monologue to a limited extent.

The fourth device has always been the least understood. This is the recording of everyday gestures, habits, manners, customs, styles of furniture, clothing, decoration, styles of traveling, eating, keeping house, modes of behaving toward children, servants, superiors, inferiors, peers, plus the various looks, glances, poses, styles of walking and other symbolic details that might exist within a scene. Symbolic of what? Symbolic, generally, of people’s status life, using that term in the broad sense of the entire pattern of behavior and possessions through which people express their position in the world or what they think it is or what they hope it to be. The recording of such details is not mere embroidery in prose. It lies as close to the center of the power of realism as any other device in literature. It is the very essence of the “absorbing” power of Balzac, for example. Balzac barely used point of view at all in the refined sense that Henry James used it later on. And yet the reader comes away feeling that he has been even more completely “inside” Balzac’s characters than James’s. Why? Here is the sort of thing Balzac does over and over. Before introducing you to Monsieur and Madame Marneffe personally (in Cousine Bette) he brings you into their drawing room and conducts a social autopsy: “The furniture covered in faded cotton velvet, the plaster statuettes masquerading as Florentine bronzes, the clumsily carved painted chandelier with its candle rings of molded glass, the carpet, a bargain whose low price was explained too late by the quantity of cotton in it, which was now visible to the naked eye—everything in the room, to the very curtains (which would have taught you that the handsome appearance of wool damask lasts for only three years)”—everything in the room begins to absorb one into the lives of a pair of down-at-the-heel social climbers, Monsieur and Madame Marneffe. Balzac piles up these details so relentlessly and at the same time so meticulously—there is scarcely a detail in the later Balzac that does not illuminate some point of status—that he triggers the reader’s memories of his own status life, his own ambitions, insecurities, delights, disasters, plus the thousand and one small humiliations and the status coups of everyday life, and triggers them over and over until he creates an atmosphere as rich and involving as the Joycean use of point of view.

I am fascinated by the fact that experimenters in the physiology of the brain, still the great terra incognita of the sciences, seem to be heading toward the theory that the human mind or psyche does not have a discrete, internal existence. It is not a possession locked inside your skull. During every moment of consciousness it is linked directly to external clues as to your status in a social and not merely a physical sense and cannot develop or survive without them. If this turns out to be so, it could explain how novelists such as Balzac, Gogol, Dickens and Dostoevsky were able to be so “involving” without using point of view with the sophistication of Flaubert or James or Joyce.

I have never heard a journalist talk about the recording of status life in any way that showed he even thought of it as a separate device. It is simply something that journalists in the new form have gravitated toward. That rather elementary and joyous ambition to show the reader real life—“Come here! Look! This is the way people live these days! These are the things they do!”—leads to it naturally. In any case, the result is the same. While so many novelists abandon the task altogether—and at the same time give up two thirds of the power of dialogue—journalists continue to experiment with all the devices of realism, revving them up, trying to use them in a bigger way, with the full passion of innocents and discoverers.

Their innocence has kept them free. Even novelists who try the new form ... suddenly relax and treat themselves to forbidden sweets. If they want to indulge a craving for Victorian rhetoric or for a Humphrey Clinkerism such as, “At this point the attentive reader may wonder how our hero could possibly…”—they go ahead and do it, as Mailer does in The Armies Of The Night with considerable charm. In this new journalism there are no sacerdotal rules; not yet in any case.... If the journalist wants to shift from third-person point of view to first-person point of view in the same scene, or in and out of different characters’ points of view, or even from the narrator’s omniscient voice to someone else’s stream of consciousness—as occurs in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test—he does it. For the blessed Visigoths there is still only the outlaw’s rule regarding technique: take, use, improvise. The result is a form that is not merely like a novel. It consumes devices that happen to have originated with the novel and mixes them with every other device known to prose. And all the while, quite beyond matters of technique, it enjoys an advantage so obvious, so built-in, one almost forgets what a power it has: the simple fact that the reader knows all this actually happened. The disclaimers have been erased. The screen is gone. The writer is one step closer to the absolute involvement of the reader that Henry James and James Joyce dreamed of and never achieved.

Novelists have made a disastrous miscalculation over the past twenty years about the nature of realism. Their view of the matter is pretty well summed up by the editor of the Partisan Review, William Phillips: “In fact, realism is just another formal device, not a permanent method for dealing with experience.” I suspect that precisely the opposite is true. If our friends the cognitive psychologists ever reach the point of knowing for sure, I think they will tell us something on this order: the introduction of realism into literature by people like Richardson, Fielding and Smollett was like the introduction of electricity into machine technology. It was not just another device. It raised the state of the art to a new magnitude. The effect of realism on the emotions was something that had never been conceived of before. No one was ever moved to tears by reading about the unhappy fates of heroes and heroines in Homer, Sophocles, Molière, Racine, Sydney, Spenser or Shakespeare. But even the impeccable Lord Jeffrey, editor of the Edinburgh Review, had cried—actually blubbered, boohooed, snuffled and sighed—over the death of Dickens’ Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop.

One doesn’t have to admire Dickens or any of the other writers who first demonstrated this power in order to appreciate the point. For writers to give up this unique power in the quest for a more sophisticated kind of fiction—it is as if an engineer were to set out to develop a more sophisticated machine technology by first of all discarding the principle of electricity. In any case, journalists now enjoy a tremendous technical advantage. They have all the juice. This is not to say they have made maximum use of it. The work done in journalism over the past ten years easily outdazzles the work done in fiction, but that is saying very little. All that one can say is that the material and the techniques are now available, and the time is right.

The status crisis that first hit literature’s middle class, the essayists or “men of letters,” has now hit the novelists themselves. Some have turned directly to nonfiction. Some, such as Gore Vidal, Herbert Gold, William Styron and Ronald Sukenick, have tried forms that land on a curious ground in between, part fiction and part nonfiction. Still others have begun to pay homage to the power of the New Journalism by putting real people, with their real names, into fictional situations.... They’re all sweating bullets.... Actually I wouldn’t say the novel is dead. It’s the kind of comment that doesn’t mean much in any case. It is only the prevailing fashions among novelists that are washed up. I think there is a tremendous future for a sort of novel that will be called the journalistic novel or perhaps documentary novel, novels of intense social realism based upon the same painstaking reporting that goes into the New Journalism. I see no reason why novelists who look down on Arthur Hailey’s work couldn’t do the same sort of reporting and research he does—and write it better, if they’re able. There are certain areas of life that journalism still cannot move into easily, particularly for reasons of invasion of privacy, and it is in this margin that the novel will be able to grow in the future.

When we talk about the “rise” or “death” of literary genres, we are talking about status, mainly. The novel no longer has the supreme status it enjoyed for ninety years (1875-1965), but neither has the New Journalism won it for itself. The status of the New Journalism is not secure by any means. In some quarters the contempt for it is boundless ... even breathtaking.... With any luck at all the new genre will never be sanctified, never be exalted, never given a theology. I probably shouldn’t even go around talking it up the way I have in this piece. All I meant to say when I started out was that the New Journalism can no longer be ignored in an artistic sense. The rest I take back.... The hell with it.... Let chaos reign ... louder music, more wine.... The hell with the standings.... The top rung is up for grabs. All the old traditions are exhausted, and no new one is yet established. All bets are off! the odds are canceled! it’s anybody’s ball game!... the horses are all drugged! the track is glass!... and out of such glorious chaos may come, from the most unexpected source, in the most unexpected form, some nice new fat Star Streamer Rockets that will light up the sky.

1. Prepared, in both instances, by New Yorker staff members, if one need edit.

2. The first of two New York Review of Books articles on “Parajournalism” (August, 1965) said: “The genre originated in Esquire but it now appears most flamboyantly in the New York Herald Tribune” ... “Dick Schaap is one of the Trib’s parajournalists” .... “Another is Jimmy Breslin ... the tough-guy-with-the-heart-of-schmaltz bard of the little man and the big celeb”.... Later the piece spoke of “Gay Talese, an Esquire alumnus who now parajournalizes mostly in The Times, in a more dignified way, of course” .... “But the king of the cats is, of course, Tom Wolfe, an Esquire alumnus who writes mostly for the Trib’s Sunday magazine, New York, which is edited by a former Esquire editor, Clay Felker....”