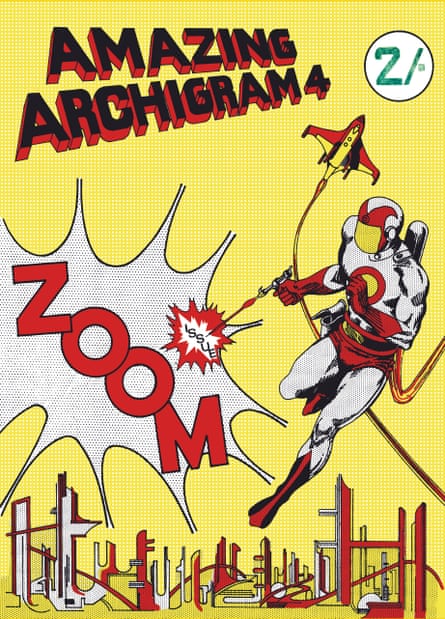

I am holding in my hand a single sheet of paper, wrapped in protective plastic, with words and drawings wriggling all over the available space, on both sides. The possibilities of offset litho printing in the year of its making, 1961, are fully explored. A pinkish splodge decorates one edge – “a potato print”, explains one of its authors now, Professor Sir Peter Cook, “to add a bit of colour”. “The poetry of bricks is gone,” intones some of the original scrawled text, “we want to drag into building som [sic] of the poetry of countdown, orbital helmets, Discord of mechanical body transportation methods.”

This document was Archigram 1, the first issue of a magazine – if a single sheet can be called that – that was to grow in pagination and significance. Its price was sixpence, in old money. “You couldn’t give it away,” says Cook, “only friends and numbskulls would buy it.”

Now, it will be literally worth its (small) weight in gold, or more, for this flimsy tablet of stone, this home-made harbinger of a technological future, is rare and collectible. It gave its name to the group of young architects who made it, a loose bunch whose interests ranged from the everyday to the extraterrestrial, who sometimes collaborated and sometimes didn’t, but the magazine gave them a common identity. They, people and publication together, would be some of the most influential of the second half of the 20th century.

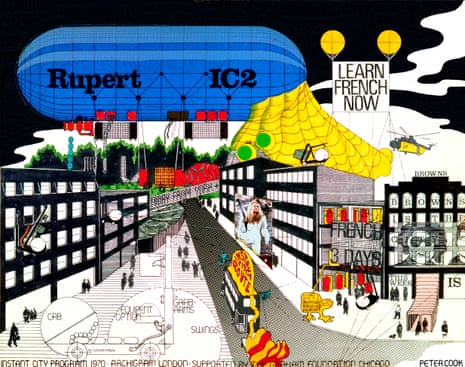

Architecture proceeds by drawing and writing as well as building – Piranesi’s engravings of imaginary prisons and actual ruins, for example, or the visions of future cities conceived by Antonio Sant’Elia, before he was killed in 1916 in the first world war, aged 28. Similarly with Archigram, whose vivid collages gave form and voice to a generation impatient with the dry prescriptions of mainstream modernists. Like pop artists at around the same time, they wanted their art form to draw energy from the explosions of technology and consumer culture that were happening all around them.

“Form follows function,” wrote another Archigrammer, David Greene, repeating a modernist slogan in order to knock it down, “no it doesn’t it follows idea, it follows a desire for architecture to be cheerful.”

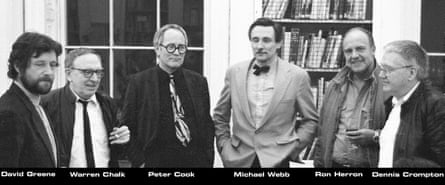

Three of Archigram’s key figures – Cook, Greene and Dennis Crompton – are sitting with me in Crompton’s house in north London. Two, Warren Chalk and Ron Herron, died too young. Another, Michael Webb, is now based in New York. The occasion of this gathering is Archigram: The Book, a 300-page compendium of the magazines and related works, assembled and edited by Crompton. There will also be events to go with the publication.

Cook does most of the talking, even when questions are directed at others. He has always been the most loquacious and media-friendly member of the group: “If we were all like Peter it would be unthinkable,” say his quieter friends.

“The period,” says Cook, “was joyfully acquisitive. Someone might be talking about powder puffs, or cranes, or enviro-pills. It was all interesting.” And so, for example, Webb came up with the “cushicle” and the “suitaloon”, fusions of shelter, vehicle and clothing, which would allow their wearers to travel around in comfortable personalised environments. Archigram wanted architecture to be as mobile, dynamic and “pulsating”, to use one of their favourite words, as the society they saw around them. They proposed buildings that moved, that shone in the dark, that could be changed at their users’ will.

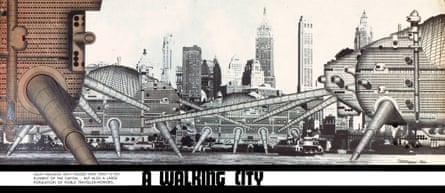

Archigram’s fascination with the technology of the moment, mostly from the US, is obvious. They loved the capsules and spacesuits that went with the Apollo moonshots, and wanted to transfer them to Earth-bound buildings. Their best-known projects – such as Ron Herron’s insect-like “Walking Cities” – look like sci-fi. Their interest in consumer culture came without the distancing irony of artists like Richard Hamilton; they were more interested in what it could achieve. “In the 1960s,” says Crompton, “self-determination became an important thing. We were interested in how the consumer could be part of the design process, not a recipient.”

At the same time they brought a British mindset to their creations, which owed as much to seaside piers as to Cape Canaveral. They drew on traditions of garden-shed tinkering and inventing, Cook says, “old gadgets, the boffin thing, Heath Robinson, bouncing bombs, funny cars”. They had a “shared sense of humour, which is a British thing. The world is so absurd, you can only make a joke or you’d collapse. You’re never as serious as when you poke fun at something.”

Cook also sees precedents in 19th-century Britain: “The Victorians were doing a lot of Archigram”, he says, in the way they combined new inventions with stylistic borrowings from wherever they fancied.

More specifically, Archigram’s was a provincial British attitude, as Cook likes to reiterate. He was born in Southend-on-Sea and studied in Bournemouth; Crompton was born in Blackpool and studied in Manchester; Greene was raised and educated in Nottingham. Cook describes how, “as a spotty boy up from the provinces”, he encountered in London the establishment culture of “English chaps… even if you were a Marxist you were an Etonian Marxist”. But “the spotties were more hungry”. They were more open-minded, more willing to learn from, for example, the lesser-known expressionist architects of 1920s Germany, rather than the canonical works of Bauhaus. Archigram, then, is partly a rebellion of the spotties against the “drearies”, as Cook and co called them, who were running the show.

The three men resist the most common charge against Archigram, that they dealt in unbuildable fantasies. “There’s nothing we couldn’t have done,” says Cook. For Greene, “We were trying to bridge the gap between what was built and what might be built.” Crompton, perhaps the most pragmatic of the gang, points to their proposals for applying light industrial techniques to building homes more efficiently, of which then, as now, there was a dire shortage. He challenges me to name an unbuildable Archigram project. Walking Cities, I venture. If you can build an ocean liner, he says, why not them?

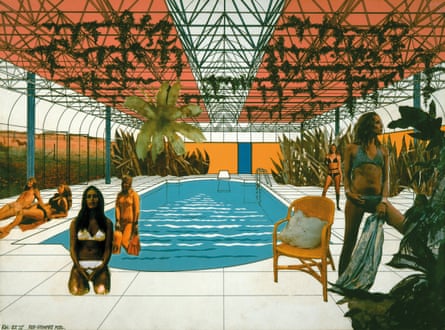

What is the case is that there are few identifiable Archigram buildings. The Southbank Centre in London, on which Crompton, Herron and Chalk played leading roles, embodies many of their ideas. A swimming pool enclosure and kitchen addition to Rod Stewart’s country house was built. The translucent, tent-like roof of Herron’s 1990 Imagination building in London was a late flowering of Archigram’s love of lightweight structures. Cook has delivered buildings, such as a bright blue blob of a drawing school in Bournemouth, in which the curvy, organic shapes from the pages of the Archigram magazine become reality.

More significant is their influence, which has filtered through their teaching into generations of students, and through their publications and exhibitions into the practice of architecture. Architects such as Nick Grimshaw (for example with his Eden Project), Rem Koolhaas and the late Will Alsop all owed something to Archigram. Their influence is most famously evident in Piano and Rogers’s Centre Pompidou, whose visible pipework and promises of dynamic change owe much to Archigram, even if Greene, for one, is ambivalent about the Parisian landmark. “They stole the look without the content,” he says. “It looks as if it could move, but it doesn’t.”

Perhaps their biggest gift to architecture is an attitude. You can pick holes in Archigram’s thinking, in particular the assumption that dynamic, free lifestyles would be best served by buildings with lots of moving parts. Some of their contraptions look like terribly contrived and complicated ways to achieve their stated ends. Greene, a quieter and more subtle thinker than Cook, realises this well himself: “The question is not ‘Can you do it?’ but ‘Why would you want to do it?’”

But running through Archigram is the essential insight that buildings should respond to the lives that go on in and around them, and that when those lives change they should be able to change too. Also the belief that, whatever you do, you should do it with zest.

It was a baggy enough group to contain differences of opinion. If Greene is “less and less interested in what things look like, compared to what lies behind”, Cook is eternally enthralled by appearance. This diversity is also one of their strengths: “so our contributors aren’t taking the same line”, it says in Archigram 2, “but they’re each taking some sort of line.”

Archigram: The Book is published by Circa Press, £95. To celebrate its publication, Peter Cook, Dennis Crompton and David Greene will join Nigel Coates at the RIBA Bookshop, 66 Portland Place, London W1 on Tuesday 20 November, 6.30pm-8.30pm, to talk about Archigram’s work

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion